What can Archaeology Tell Us About Greek Religion?

Sep 13, 2024Religion is an ephemeral and hard to define concept, one that is often tied up with notions of tradition, culture, belief and ideology. It is nevertheless one of the aspects of Greek culture that people remain fascinated with. Archaeologically, we are perpetually faced with the challenge of defining religion. The positivism and empiricism of processual theory often assumes that objects from the past are inherently archaeological in that they are data or part of an objective “archaeological record.”

The positivist epistemology of processualism conflates the signifier with the signified. By adopting this epistemology, previous generations of archaeological theory put forward a view that objects are the label themselves rather than that which is described by the label. The idea that meaning is inherently fixed in an object and that we must have a research question that will make a priori sense of that meaning denies that sites or artefacts can have meaning, and thus value, outside of a scientific framework. This framework of logical positivism doesn’t work in the context of religion, as objects, places and symbols can have multiple meanings in different contexts that reflect cultural dynamics.

We have an inherent Abrahamic bias in the Western World. When thinking about religion, there is a tendency to assume institutionalised models, often time with clearly defined clergy, holy books, strict notions of deities among other things. Historically though, this model is relatively recent and works for very few cultures in the ancient world. Both the Egyptians and Yucatec Maya alike did not even have a word or concept for religion as a separate category or way of living as we do in secularist society. The relegation of religion to a clearly definable and othered category is a post-enlightenment consequence.

Modern pillars of what we think of as religious philosophy, things like sacred texts, moral codes and the promise of immortality did not exist in the same way in Greece. Part of the necessity and appeal of itinerant philosophers or sophists lies in their ability to articulate such moral codes. Archaeologically then, we can discuss various constituent parts that make up what we characterise as religious behaviour, especially those that leave remains to be studied.

For ancient Greek religion then, we can study elements such as sacrifice, votives -including things like dedications and libations, iconographies that embed polytheistic and mythological narratives, especially those that reflect changes in politics or society, as well as socially informed notions like asebeia or pollution, giving an idea of ethics or the treatment of various groups. Concerns with the dead are also ever present, especially notions of the afterlife and the proper treatment of bodies, which equally opens up discussion around notions of competition.

These things considered, Greek religion can generally manifest archaeology in primary ways. There are the household or local deities, usually related to families or cities, the Symposium -during which libations would be poured for ancestors, the agathodaimon or those not present, and more popularly, the Deme Erkhia -sacred calendar. Between 375-50 BC, sacrifice was conducted publicly in or outside temples on behalf of at least 43 deities and heroes, many of which have bled through into the modern Western Imagination.

Alongside these public manifestations, we can also speak of more privatised elements such as the Mystery Cults, open only to those initiated and perhaps retaining elements of older Late Minoan/Early Mycenaean theology, and the Hero Shrines, frequently dotting the landscape as pilgrimage or oracle points such as the Cave of Trophonius. Religion is inherently centred on expression, it’s not so much about what’s in your head, but about what you do in practice. By understanding it as something performative, we can bridge it archaeologically. By reversing the process, religious expression can give us insight into how ancient Greek people structured their minds and thought about the world.

It’s equally impossible to study or consider religion in isolation. As a tool of the state, religion intersects politics, social and ethical systems, and holds economic implication for trade and exchange. When it comes to things like pilgrimage, consulting oracles or hero cults, we are also looking at aspects of social mobility. Major sanctuaries like Delphi, Olympia and Delos are panhellenic in the sense that everyone across Greece would have known them, and as I covered in a previous episode, such places also held political roles as neutral ground for state negotiation.

The origins of Greek religion as we understand it date back to the Early Bronze Age, with various votives and figurines attesting to continuity in iconography from Minoan and Mycenaean cultures. Places of great religious importance are seen to be active from the late Neolithic, and seem to have been in constant use even up to later periods. Elements do not hold true across the board though, as Greek religion was heavily regionalised and not consistent everywhere. Each city state would have its own values and history which informed the perspective and lenses through which deities were worshipped there. Sometimes, what’s going on on Crete has very little connection to what’s going on on the mainland, religiously speaking.

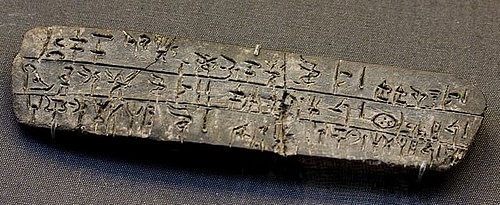

Linear B Mycenaean texts can be useful in reconstructing elements of the Bronze Age pantheon, but are of limited use for post-homeric conceptions of religion as deity roles, epithets and myths are often markedly different.

Cultic places and shrines on the other hand, are much easier to establish continuity with. Olympia for example has clear evidence of altars dedicated to Zeus from the Late Bronze Age. While the sacred tradition may have eventually culminated in the Olympic Games, the place and land itself appears to have had religious or sacred significance since the Bronze Age.

The Idaean Cave on Crete equally seems to be an incredibly ancient pilgrimage site.

Excavations have frequently turned up evidence dating back to the Neolithic as early as 6000 BC, coupled with very popular use during the Iron Age, testified especially by an incredible number of votive ivory deposits. Mythologically, both locally on Crete and throughout Greece, Idaea is the cave in which the infant Zeus was raised in hiding from his father Cronos. It appears to have been such a significant site that even the Romans erected an altar to Jupiter outside of it in the post-Hellenistic period.

Interestingly, situating religion in wider society helps us understand that some of these sacred sites are not just about mythological narratives, but also control of resources and political messaging.

Water, especially rivers, seem to have been frequently personified and sacralised by local populations, signalling a desire to engage dialogue around who can control them or have access to them. Identifying such places as religiously significant then, can equally serve as a way for local political units to exploit the landscape, reinforce culturally significant boundaries and delineate access depending on status. We can also often turn to iconography studies to better understand stories and their evolutions.

For instance, this votive deposit of a man fighting a centaur, found at Olympia and dating to 750 BC seems to echo similar motifs that we see 3-400 years later during the Classical and Hellenistic periods.

Are these artefacts depicting variations of the same story or myth? Or have such myths changed and adapted through time? How can such variations inform our understanding of how each period or society saw themselves and their relationships with their neighbours?

Another dimension of religion that archaeology can be especially useful in is architecture. Greece is naturally famed for its temples, but prior to the marble sophistication we know and love, interestingly the earliest temples and religious structures that we know of such as the 8th century Temple of Apollo in Eretria look remarkably like domestic houses, such as the Geometric one from Perachora.

There appears to be a concerted effort to emulate the Megaron throne room from the Mycenaean palaces in early religious architecture, perhaps in an attempt to echo the power such rooms once had. In many ways, religious and sacred architecture appears to be modelled off of early domestic structure. Even in the Late Bronze Age Mycenaean culture though, the palace Megaron itself can be seen as a scaling up of basic village domestic architecture.

Centering back on such local religious expression naturally allows us to focus once again on Hero Cults. These fascinating localised shrines are first attested in Homeric Literature, but frequently are administered and thought about differently depending on the region. You may remember the EIA site of Lefkandi and its famous Heroon surrounded by wealthy cemeteries. This is an archetypal way of recognising a hero cult, having a central burial of an important figure, surrounded by graves of the community, wanting to be buried as close as they can to the original body.

While the archetypal hero is usually a city’s eponymous founder or someone significant to the community, that also changes with the advent of Athenian democracy. The tumulus of Marathon for example, was created by Athens to commemorate the battle that -for them, defined Athenian identity, and yet, for all intents and purposes, they appear to have treated it in a similar manner to a Hero Cult. This shrine was not about a single individual, but a community and group who had fought a battle.

Sources

Barrett, C. E. 2015: Material evidence in Eidinow, E. and Kindt, J. The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Greek Religion. Oxford University Press

Ekroth G. 2017: Bare bones: zooarchaeology and Greek sacrifice, in S. Hitch and I. Rutherford (eds) Animal sacrifice in the ancient Greek world. Cambridge

Legarra Herrero, B. 2012: Cemeteries and the construction, deconstruction and non-construction of hierarchical societies in Early Bronze Age Crete. In, I. Schoep, P. Tomkins and J. Driessen (eds) Back to the Beginning: Reassessing social, economic and political complexity in the Early and Middle Bronze Age on Crete. Oxbow Books

Morgan, C. 1993: The origins of pan-Hellenism in Marinatos, in N. and R. Hägg (eds) Greek Sanctuaries: New Approaches, 18-44

Scott, M. 2010: Delphi and Olympia: The spatial politics of panhellenism in the archaic and classical periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

S. Lemos, 2009: Lefkandi in Archaeological Reports 2007-2008 (eds C. Morgan et al)

Burkert, W. 1985: Greek Religion: Archaic and Classical, Harvard University Press

Lewis R F. 1896: Cults of the Greek States 5 vols. Oxford; Clarendon

Don't miss a post!

Sign up to get notified of when I upload as well as any new classes delivered to your inbox.

I hate SPAM. I will never sell your information, for any reason.