Greek Sanctuaries & Votive Deposits

Sep 16, 2024One of the best insights we can garner into Greek religion archaeologically is looking at the physical manifestation of its temple sites, mainly, its sanctuaries. The first and largely most popular or well known in the modern day are Civic Sanctuaries, the type site being the Athenian Acropolis.

Many Greek city-states would have had something along the same lines as the Acropolis in Athens, but not usually as monumental or developed. The Athenian Acropolis is not just a temple site to Athenia, it is a monument to Athenian Imperialism, signalling the wealth and sophistication of the Polis to the outside world.

Usually, these Civic Sanctuaries will be highly nationalistic in nature, related to the direct community, their city deity or local hero. This nationalistic tone makes sense when you consider that many Civic Sanctuaries would have been community building projects, involving people from all aspects of society giving something of their own to the temple complex. In this way, as much as this religious complex is about the community’s relationship with divinity, it is also a way in which the interior members can define themselves as a group against outsiders.

One notable exception to this is the Graeco Egyptian site of Naukratis. This site was a city and Greek trading-post in Egypt, located on the Canopic branch of the Nile, south-east of Alexandria. It was the first and, for much of its early history, the only permanent Greek settlement in Egypt, serving as a symbiotic nexus for the interchange of Greek and Egyptian art and culture. While we have evidence of Graeco Egyptian interaction as far back as the Minoan period, it remained purely economic until the 7th century where Herodotus relates a story of Ionian and Carian pirates forced by storm to land near the Nile Delta, eventually entering the service of the 26th dynasty pharaoh Psamtik I.

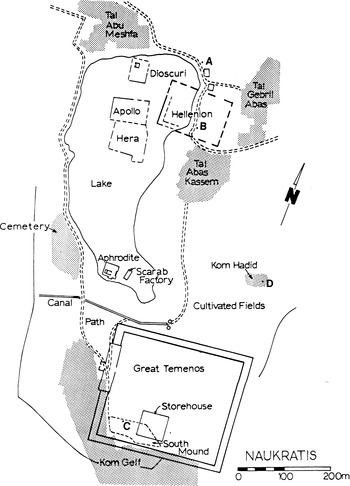

As Greek settlers arrived in Naukratis, they were allowed to situate themselves, and began the process of colonisation. In an effort to create something that they could identify themselves with, some of the earliest constructions at Naukratis are temples. Following excavations by Flinders Petrie, we have evidence of temples to Apollo, Hera, the Dioscuri and Aphrodite. According to Herodotus however, there was a sacred building known as the Hellenion. Remarkably, the votives found inside the Hellenion come from all over the Aegean, most commonly the East Aegean. Interestingly though, a large portion of inscribed ostraka and pottery from the Hellenion is dedicated to the “Gods of the Hellenes” and "all the Greeks".

This is remarkable case of projecting a unified identity in a foreign nation. Naukratis is one of the first and only temples seemingly open to all Greeks, regardless of city-state or allegiance. This gives us insights into just how different the Naukratian Greeks were and the particular challenges they may have faced establishing themselves abroad.

One can’t help but wonder how new radical political identifications rippled back into mainland Greece and helped to foster notions of panhellenism like we see in Homer. These places that are on the fringes of the Greek world are counter-normative, and often end up feedbacking into more conservative elements of Greek society and disrupting standard ways of thinking.

The other major type of sanctuary we often see are what we can tentatively call Extra Urban ones. These religious sites are seldom near a city, but will often be administered by one. A great example of this type of sanctuary is Perachora, a kind of harbour sanctuary located on a promontory on the Corinthian Gulf.

This strategic position historically connected the Attic regions with the Penepolese, meaning that its East and West entrances were the only viable ways in or out of the region by sea. This sanctuary appears to have been controlled primarily by Corinth, although they seem to have minimised public portrayal of this control, allowing relatively free movement through the area. In a way, they seem to have stressed the political neutrality brought about religious spaces here, acting a wayfare position for travellers and traders.

Unsurprisingly, we have a wide assemblage of votive materials here, primarily brought by sailors and merchants. Items from all over the Eastern Mediterranean such as Phonaecian scarabs, Mesopotamian ivories, Italian metalwork and personal effects are frequently found as offerings to sea deities, usually to ensure protection during travel.

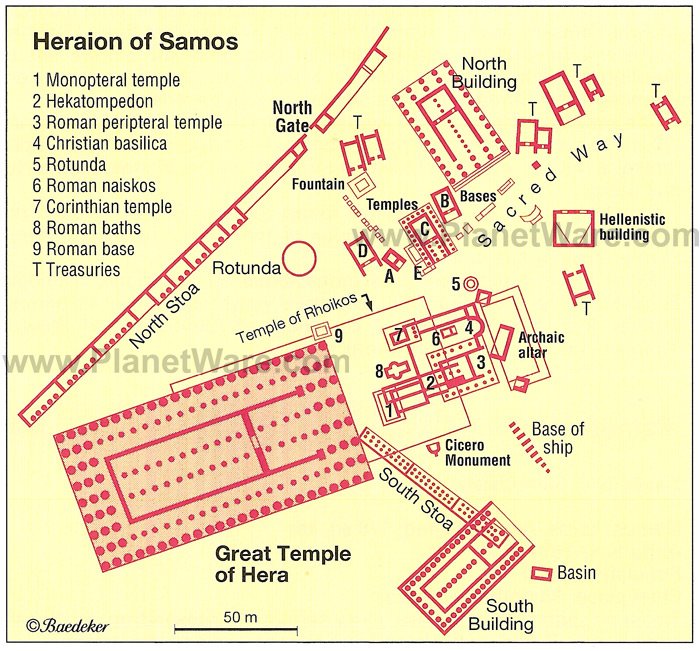

We actually see a similar situation in Samos with the famous temple of Hera there, known as the Samos Heraion. Geographically, Samos is another one of those in-between places, situated between the Aegean islands and Anatolia and yet vastly rich in resources. It became a primary gateway for people coming into Greece from Mesopotamia and Anatolia, bringing not only material culture with them, but also ideological in the form of cults, mysteries and religious ideas.

Like Perachora, the Heraion was administered by the polis in Samos, but not markedly. As an in-between ritual sanctuary, they allowed free movement and cultural exchange. Archaeologically, this is incredibly clear to us, as the site is chock full of Anatolian and Mesopotamian ivories, bronzework of Egyptian, Ugaritic, Cypriot and Assyrian origin, prestige items like cauldrons and statuettes and even crocodile and antelope bones and model ships. We can really think of Samos as a major point of contact between the Ioanian Polis and Anatolian kingdoms, both materially and ideologically, something that extends all the way back to the Early Bronze Age, 2000 years prior.

While we often think of votive deposits as instrumental to religious practice, archaeology reveals some interesting caveats with this. Much work has been done on tracing the typology and province of votive offerings at sanctuary sites, and what they can tell us about Greek ideology and history. Interestingly, votive deposits actually don’t seem to be very popular until we get into the 8th and 7th centuries BC. This seems to coincide with a diminishing of importance in the sphere of burial from the 8th century onwards.

What this can tell us is that around the time of the rise of public sanctuaries, there was an ideological shift in Greek religion away from burial and the dead -a sphere where it is much easier to show your own power and prestige, towards votives in temples and more personal ornamentation. Rather than relying on tombs or burial circumstances, the markers of societal differentiation shift to votive deposits. This change also reflects and arguably anticipates the polis and civic sanctuary, in which religious expression is becoming more public, communal and monumental.

In other words, the act of offering prestige objects is itself an act of displaying status in front of a larger audience and community, one which marks a shift away from depositing such material in graves and cemeteries to public locations. All of this is reflecting wider societal, political and economic changes in the Greek world, especially related to social organisation. Religious sanctuaries took on an inherently political role as a means of marking the territory of a polis, all the while reflecting wider cultural and economic roles as meeting points for state discussions.

At the same time, we must also distinguish the panhellenic sanctuaries, primarily Olympia and Delphi. Olympia is a fairly well known site, but there are still questions around it. It’s worth pointing out that both Olympia and Delphi are really in the middle of nowhere, they are not near any major polis centre. From an economic and practical point of view, this is strange. While there were local polises around Olympia, none of them ever became big players in the city-state scene. This does partly work to its advantage though, as it is precisely for the reason that there are no big-interest players administering the site that Olympia became so popular. The site was an enormous open field in which no single city-state felt threatened by any other.

Olympia’s distance from the rest of the “civilised world” equally contributed to its sense of remoteness and sacredness, and lessened the political or mundane baggage that often weighed down the Civic and Extra Urban Sanctuaries. A lot of work is being done on understanding the chronology of Olympia, especially with tracing how far back into history it goes as a sacred site. We have enough evidence to suggest that it was considered important during the Bronze Age, and especially the Early Iron Age. While it is famous today for the Olympic Games, it was likely a cult site to Zeus first, with the dedication list of Hippia containing the first winners of the games dating to 776 BC. Unfortunately, the majority of archaeology can only be dated to 700 BC onwards. While we know things went on there prior to this, they don’t leave good remains as evidence, so connecting the earlier phases of cultic activity to the later ones is a difficult task.

The majority of votives at panhellenic sites come from aristocratic families, usually in an effort to bolster their own standing and position within their local polis. While civic aspects are present, many aristocratic nobles are keen to identify themselves as the direct offerer, all in effort to show off, not just to the gods but also other polises or families within their own polis.

The sanctuary of Delphi is a little different to Olympia, and we have different questions surrounding it. Unlike Olympia, Delphi was purely religious, associated with the Pythian Oracle rather than games. Architecturally, the place is a marvel, being built into and above the mountain range and clearly designed to elicit a phenomenological sense of awe as you walk through the temple system. Interestingly though, on your way up to the temple of Apollo to consult the oracle, you would have had to go through two treasuries, that of the Syphnians and the Athenians. These treasuries were governmental buildings in which each polis not only stored wealth but also their votives, usually dedicated to Apollo.

Naturally, as you’re walking through these buildings, it's a chance for the polises to compete and show off their respective wealth and power. This is embodied not only in the votives and material wealth, but also in the masonry quality of the buildings themselves, testifying to superior artistry and cultural tradition, something Athens was very interested in dominating.

A lot of the statuary in Delphi is Athenian in nature, especially famous ones like the Delphi Charioteer, which has the added bonus of associating Athens with Delphi in the public mind.

In total then, we can think of sanctuaries as embodying marginality and being inter-space regions that embody liminality. Rather than divorcing them from wider society, it pays to be aware of their large scale political, social and economic roles as a mechanism for the creation of elite power or democratisation. Nevertheless, they were instrumental in the development of ideals of Greekness, panhellenism and national identity.

Sources

Ekroth G. 2017: Bare bones: zooarchaeology and Greek sacrifice, in S. Hitch and I. Rutherford (eds) Animal sacrifice in the ancient Greek world. Cambridge

Hitch S. and I. Rutherford (eds) 2018: Animal sacrifice in the ancient Greek world. Cambridge

Johnston A. 2001/2002: Sailors and sanctuaries of the ancient Greek world in Archaeology International, 25-28

Eidinow, E. and Kindt, J. (eds) 2015: The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Greek Religion. Oxford University Press.

Pedley, J. 2005: Sanctuaries and the sacred in the ancient Greek world. New York: Cambridge University Press

Morgan, C. 1993: The origins of pan-Hellenism in Marinatos, in N. and R. Hägg (eds) Greek Sanctuaries: New Approaches, 18-44

Scott, M. 2010: Delphi and Olympia: The spatial politics of panhellenism in the archaic and classical periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Demetriou, D. 2012: ‘Naukratis’, in Negotiating Identity in the Ancient Mediterranean: The Archaic and Classical Greek Multiethnic Emporia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 105–152.

Don't miss a post!

Sign up to get notified of when I upload as well as any new classes delivered to your inbox.

I hate SPAM. I will never sell your information, for any reason.