Urbanisation in Archaic Greece | What Made a Polis?

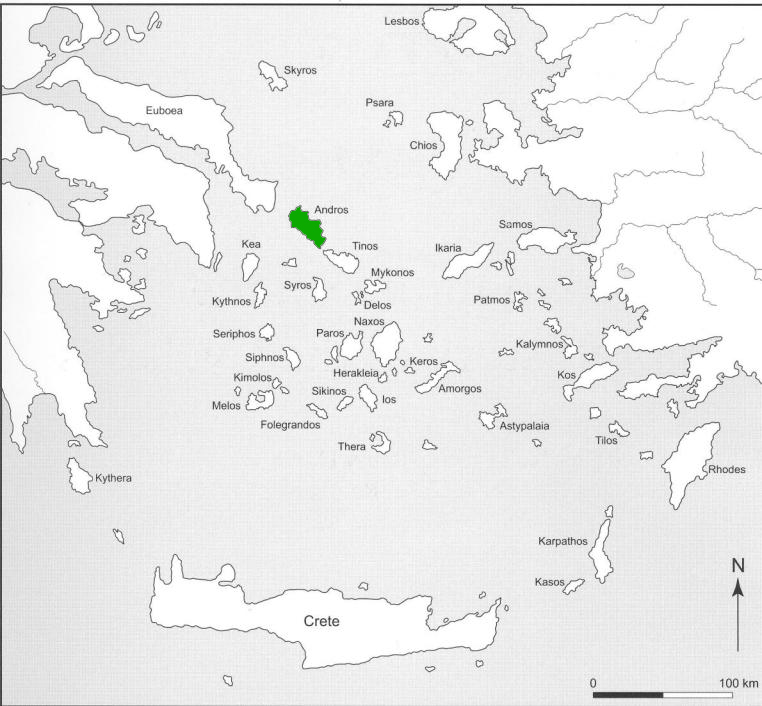

Jul 01, 2024To begin understanding the nature of the early Polis, we can go back to the end of the Early Iron Age, focusing on the period between 900-700 BCE. This period is naturally hard to discern, with most of the remains being underneath the Archaic layers & stratigraphy, since many Polises were continually in use during the transition period. One major exception to this is the settlement of Zagora on the island of Andros. This Early Iron Age settlement has been preserved undisturbed by later occupation and is renowned for its extensive 9th-8th century village, with some indications that it may have been occupied in the late 10th.

Now, it’s worth pointing out that Andros as an island is tiny and quite remote, so it’s not the best site to give us a picture of what’s happening in the more central Aegean states, but Zagora is nevertheless one of the better preserved sites from this period. On the surface, Zogra is a larger settlement than you might expect for such a tiny island like Andros, covering an area of about 6.7 hectares, which tells us something about the wider relations & trading influence that was going on. Over 90% of the decorated pottery there is imported; originating from its fine ware pottery producing neighbours, including Euboian towns such as Eretria and Lefkandi, and islands such as Naxos and Paros, as well as Athens and Corinth further afield.

Australian excavations carried out between 1967 and 1974 uncovered around 10% of the total settlement area, which had 55 definable stone built rooms which together represent at least 25 houses, organised in neighbourhood clusters very similar to how Greek island villages are organised today.

Interestingly, one of the defining features of the Zagora houses is that they are rectilinear rather than circular like the previous generation of domestic structures. The rectilinear structure is naturally better suited to neighbourhood planning, grid design & expansion. While some of the early houses had one or two spaces, the Zaograns appear to not only have frequently added spaces and extra rooms as time went on, but also specialised those spaces, demarcating kitchens from living quarters and storage from production. So we can see that the basis for urban planning and architecture is already in place in the 9th & 10th century, but also that it is increasingly becoming more and more complex.

As well as domestic housing, an impressive fortification wall with a well-protected gate was also found there, as well as a sacred area, which seems to have continued to be visited after the settlement was abandoned at the end of the 8th century. The overall cult throughout the Aegean during this time is going through a marked shift, notably with the emergence of the first pan-hellenic sanctuaries at Olympia & Delphi.

These regional sanctuaries are incredibly important for defining the idea of Greekness. Olympia & Delphi really are in the middle of nowhere, they are not near major Polises, meaning people really have to go out of their way to get to them. They play a crucial role in pulling together the identity of the independent Polises into a “Hellenic” identity at a macro scale. At the level of the city, we are looking at a Micro Cult, involving local gods or heroes, but at these regional sanctuaries we are seeing areas where peace is enforced & no clear ownership is shown, meaning these are inter-state cults. Even if the local Polises hate each other, they still need each other, whether for trade & exchange or treatises, and places like Olympia & Delphi help facilitate this.

According to data from Ian Morris, who was focusing on Athens during this time period, we are probably looking at population ranges between 200,000-400,000 people in a Polis, which is about the same size as a modern London borough, which naturally requires a strong level of organisation. To give a stark contrast however, data from the Hellenistic Period for three Polises on Crete; Tarrha, Araden & Anopolis in the area of Sphakia appear to have had populations of anywhere between 400 and 1000 people, even in the Hellenistic! These three cities still self identified as a Polis and operated autonomously, they just never expanded. So again, we can not use size or complexity to define a Polis. While I will focus around Athens for the remainder of this post, it is actually more of an exception than a standard.

Along with Athens, sites like Knossos, Sparta, Argos and Corinth can give us a good picture of what’s going on, but also the colonies in Magna Graecia, as it is around this time that we start seeing the earliest Greek colonies in Southern Italy. One of the most remarkable sites for studying the emergence of a Greek Polis colony is that of Megara Hyblaea in Sicily, not far from Augusta on the east coast, 20 kilometres northwest of Syracuse. This city is remarkable because it appears to have been built completely from scratch, with no prior deposits. Naturally, this tells us a huge amount about the Greek’s own conception of what makes a city and what they felt was necessary as they were starting from the ground up.

We have all the usual areas and dimensions of a city that we know from other 8th century Polis sites, things like a central Agora, some cult spaces and clear evidence of urban planning in the form of streets. Hyblaea also seems to have been walled, not so much around the central urban zones, but simply to demarcate territory. Strangely, a large amount of the cult spaces in this city were actually on the edges, almost outside the city proper. They appear to be creating sanctuaries here as a means of claiming the space for themselves ideologically.

Athens

Undoubtedly however, the Polis with the best evidence from the Early Iron Age is Archaic Athens. In recent years, many Greek archaeologists have begun structural and translation movements to pull together past decades of scholarship and make it available to the international community, which has given us a much fuller understanding of the city as a whole.

Back in the 1980s, Ian Morris proposed the idea of how we should look at the development of Athens as a whole in an effort to understand state formation. Naturally, as I mentioned in the last episode, one of the major challenges with Athens is that it is still a major inhabited city, so much of the archaeology is below modern day residential and public areas. Morris sought to get around this problem by shifting focus to the numerous tombs in the area, and examined the grave goods, burial styles and frequency of internments or cremations in an effort to understand the transition between the Geometric to the Proto Attic periods.

What he saw was that around 700 BCE Athens underwent a change in how it was organised. Prior to the beginning of the 8th century, Athenian tombs and minor settlements were far more spread out in the region, signalling potentially different communities, but it was around that 700 mark that we saw a new level of social organisation and cooperation. Not only do the major settlements begin to nucleate, but they begin moving the cemeteries further and further away, to the outskirts of their territories, which would later become defined by the city walls.

In 2003, the Greek archaeologist John Papadopoulos proposed an alternative model to Morris’. Papadopoulos took issue especially with the Kerameikos neighbourhood northwest of the Acropolis, which included an extensive area both within and outside the ancient city walls. In later Classical Athens, it was the potters' quarter of the city, and we actually get the English word "ceramic" from it! It was also the site of an important cemetery and numerous funerary sculptures erected along the Sacred Way, on the road from Athens to Eleusis.

Papadopoulos noted how the Agora was referred to as the “original Kerameikos” in certain texts, and that the new one (which would have been a major production centre) was theoretically moved outside of the city walls during the time it was supposed to be expanding. For him, there was not strong enough evidence to suggest Morris' assumption that there were different communities in the vicinity. Instead, he argues that Athens was a nucleated settlement much earlier. In theory, we simply can’t see the central portions of the Archaic State because they are most likely located in or around the Acropolis, which -if you remember, is also where the Mycnaean settlement was before.

Instead, the majority of external “settlements” are in fact cemeteries, until around 700 where the city gets bigger and starts to push outwards. In other words, where Morris argues for a nucleation and centralisation, Papadopoulos argues for a pushing out and expansion. In the last few years, a lot of work has been done on harmonising these two approaches. Especial focus has been given to the Submycanaean period, with the focus being on digitising and charting all of the various test pits and holes that have been dug for pipe or infrastructure work over the past decade to produce a picture that post-Mycenaeans, the main evidence for settlement is around the Acropolis. Just because the main settlement is centred around the hill however, doesn’t rule out the possibility of smaller local settlements around it though.

As we move into the early & middle Geometric period, things become complicated, in light of the boundaries for the Kerameikos, the agora and the cemeteries. The primary evidence for settlements comes from wells and production zones and mortuary spaces at the same time.

The chronology here is difficult to pin down. Having wells in a cemetery doesn’t make much sense, but they are usually associated with production zones, on account of the water needed to produce ceramics. As we look at more details, even the pottery in the old Kerameikos area looks similar to that in the cemetery, with some of the cemetery pottery likely being earlier, meaning that the site of old cemeteries eventually transformed into a production area for ceramics as the city expanded. In other words, the data seems to support Papadopoulos’ argument that as the city expands, the regions on the outskirts, which used to be occupied by cemeteries, become re-defined as production zones.

On the level of the people and culture, we equally see major changes happening at the turn of the 7th century. Cremations appear to replace inhumations, which creates a decline in tombs -potentially explained as increasing social stratification so that only upper classes can use them, and we see a rise in child burials coinciding with a reorganisation of the city toward the end of the Geometric II. As we move into the Archaic period proper, we see a lot of these structural changes becoming more defined. By the early 6th century, habitation moves further out, and the Agora becomes much more of a public space over and above a production zone. This coincides with figures such as Solon, and the rise of civic duty. It is during this period that the Acropolis appears to have taken over as the dominant cultic place, and the political and economic functions of the city move into the Agora and they expand.

A major question still remaining is how the Athenians controlled the wider region of Attica, as they relied on it as their hinterland. Attica was very rich in silver, which made Athens very rich in the later Classical period.

In the end, there is no one way toward urbanism for the Greek states, some are clearly the result of agglomeration such as Sparta, while others such as Athens are more focused on nuclearisation, so Polis formation is clearly not a homogenous process. How we define a Polis also needs updating and consideration, as small scale states raise questions about the relationship between the centre and the hinterland.

This outline considered, we are now ready to look at the Classical city.

Sources

Televantou, C. 2008: Strofilas: A Neolithic Settlement on Andros. in Brodie, N., Doole, J., Gavalas, G. and Renfrew, C. eds., Horizon. A Colloquium on the Prehistory of the Cyclades, Cambridge, 43-54.

Zagora Archaeological Report. [Online]. Available at: https://zagoraarchaeologicalproject.org/the-site/about-zagora/

Angelis, F. 2002: Trade and Agriculture at Megara Hyblaia. In: Oxford Journal of Archaeology 21.3, 299-310

Morris, I. 1991: The early polis as city and state. In J. Price and A. Wallace-Hadrill (eds) City and country in the ancient world, 25-57

Papadopoulos, J. 2003: Ceramicus Redivivus: The Early Iron Age Potters’ Field in the Area of the Classical Athenian Agora. Hesperia Supplement 31, The American School of Classical Studies at Athens.

Dimitriadou, Eirini M., 2019. "Child Graves of Submycenaean and Geometric Periods" for Early Athens: Settlements and Cemeteries in the Submycenaean, Geometric, and Archaic Periods. Version 1. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press

Dimitriadou, Eirini M., 2019. "Submycenaean, Protogeometric, Early/Middle Geometric, Late Geometric, and Archaic Periods" for Early Athens: Settlements and Cemeteries in the Submycenaean, Geometric, and Archaic Periods. Version 1. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press.

Tréziny, H. 2016: Archaeological data on the foundation of Megara Hyblaea. Certainties and hypotheses. DONNELAN L.; NIZZO V.; BURGERS G.-J. Conceptualising early Colonisation, Brepols, pp.167-178. 978-90-74461-82-5

Mégara 7 : H. Tréziny (dir.), avec la collaboration de Fr. Mège, Mégara Hyblaea 7. La ville classique, hellénistique et romaine, Rome 2018 (Coll. EFR 1/7).

Alagich, R., Trantalidou, K., Miller, M.C. et al. 2021: Reconstructing animal management practices at Greek Early Iron Age Zagora (Andros) using stable isotopes. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 13, 9

Fachard, S. 2021: Asty and Chora: City and Countryside’, in J. Neils and D.K. Rogers (eds.) The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Athens. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (Cambridge Companions to the Ancient World), pp. 21–34.

Don't miss a post!

Sign up to get notified of when I upload as well as any new classes delivered to your inbox.

I hate SPAM. I will never sell your information, for any reason.