Urban Planning in Classical Athens

Jul 08, 2024Following the rise of the Archaic Polis of Athens, I would be amiss if I didn’t at least spend one post on the Classical city to talk about it a bit. The easiest way to begin talking about Athens in the Classical Period is through its architecture. It is usually even defined by it! When most of you think of Athens, you are immediately drawn to its monumental and sculptural masterpieces. In the Classical Period it had a central city complete with the Agora, which defined its economic and legal identity as well as a high citadel in the form of the Acropolis which served the function of defining its religious character.

It was surrounded by extensive defensive walls that have their origins in the Bronze Age, which -as I mentioned, are most likely Mycenaean, and they were rebuilt and extended over the centuries. There were in fact three long walls all together; but the name Long Walls seems to have been confined to the two 4.5 mile ones leading to the Piraeus, the famous port city within the urban district mentioned by Plato in the opening of the Republic, while the wall leading to Phalerum -the port, was called the Phalerian Wall. The entire circuit of the walls was around 22 miles in length. These walls cannot be understated, not only did they serve a defensive purpose, but an ideological one. For the Athenians -as with other Polises, the inside of the walls demarcated the civilised word, while all that existed outside of them was seen as the wild unknown.

Found interspersed along these walls were the famous city gates. The majority of these were on the Western side. Beginning with the Great Dipylon, the most frequently used gate of the city, this led from the inner Kerameikos to the outer Kerameikos, and further down to the Academy. Deeper inside the Kerameikos lay the Sacred Gate, famous for being the start point of the sacred road to Eleusis used during Mystery Processions. Another gate known as the Knight's Gate was probably between the Hill of the Nymphs and the Pnyx, a local hillside inside the city where men would meet for assembly in the Democracy. Toward the Long Western Walls lay the Piraean Gate, between the Pnyx and the Mouseion, leading to the carriage road to the Piraeus. Finally there was the Melitian Gate, named because it led to the Deme Melite, a further suburb within the city.

On the Southern side lay the Gate of the Dead in the neighbourhood of the Mouseion, so named for its proximity to the cemeteries. The Itonian Gate also lay to the south of the city, and marked the point where the road to Phalerum began. On the East side was the Gate of Diochares, leading to the Lyceum, the famous gymnasium that was dedicated to Apollo Lyceus. Eventually this lyceum became the location for the Peripatetic school of Aristotle. The Diomean Gate equally lay to the East and lead to Cynosarges, the famous temple of Heracles and sacred grove just outside the walls. Finally, on the Northern side lay the Acharnian Gate, which led to the Acharnai suburbs.

Personally, the thing that strikes me more about Classical Athens though are its roads and processual highways. These vast trackways often connected entire districts with the hinterland and were frequently used for religious and civic processions such as the Panathenaic Festivals coming out of the Dipylon Gate. Alongside this though, the advanced road systems helped to create an expertly structured city that made use of concentric planning in which the main parts such as the Agora and the Bouleuterion -which was the central building of the assembly, could meet in the middle before gradually moving to the residential suburbs closer to the outer walls.

A lot of interest has been devoted in recent years to Hippodamus of Miletus, the Greek architect who is now considered to be "the father of European urban planning.” Born in Miletus and living during the 5th century BCE, Aristotle defined him as the first author who wrote on the theory of government, without any knowledge of practical affairs. He was one of the first to set out plans for how a city should look and function with its various districts and is largely credited with designing the layout of the Piraeus around 451 BCE, which he orchestrated to have wide streets radiating from the central Agora, which was actually called the Hippodameia in his honour.

His plans of Greek cities were characterised by order and regularity in contrast to the intricacy and confusion common to other cities of the early Classical period.. He is often seen as the originator of the idea that a town plan might formally embody and clarify a rational social order with well defined spaces & a logical distribution. The modern city of Manhattan is even still based on his work!

Olynthus

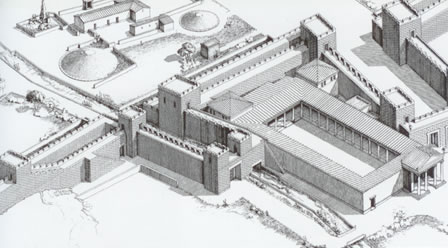

Another interesting site to talk about during this period to help contextualise Athens is Olynthus, an ancient city in present-day Chalcidice. Olynthus flourished between 432 BCE until its destruction by Phillip II of Macedon in 348 BCE. It was finally abandoned in 316 BCE. It is one of those cities in which we have a very good window into a specific period as it has very little Hellenistic or later era architecture, meaning that the archaeology there is almost unanimously of the Classic Period and was never built over. The archaic city appears to have been built under a provincially urban plan and extended throughout the whole south hill. Two avenues were found along the eastern and western edges of the hill that intersected with crossing streets. But along the south avenue shops and small houses were found while the administrative part was located in the north part of the hill, where the agora and a deanery were found.

The Classical city was founded on the much larger north hill and spread out to its eastern slope. Like Athens it had an Acropolis and old city situated on the south hill, but as we look to the north we can see noticeably Hippodamian style planning. The largest part of the town was excavated across four seasons, spanning from 1928 to 1938 and gives us a window into Classical Urban life.

Its plan looks surprisingly modern, with two large avenues with an amplitude of 7 metres, along with vertical and horizontal streets that divided the urban area into city blocks. Each one had ten houses with two floors and a paved yard. While there were certainly larger villas, signifying richer members of the community, in general the majority of the population lived in very similar styled houses, usually having interior patios with hexagonal floor plans to help designate different spaces.

The sheer uniformity of Olynthos tells us a lot about what we might call the Greek Middle Class. The standard house type appears pretty uniformly across the board except for a small number of rich villas that were excavated in the aristocratic suburb of the city located in the eastern part of the north hill which contain some of the earliest floor mosaics in Greek art. There are however still questions in relation to a lot of things here, mainly around activity use. What kind of activities were done in the homes, and by whom? Are these agricultural homesteads or living inside the city? Were there gendered areas for men and women?

Olynthos is still currently being excavated to answer these questions, and a large focus is around textile production zones. If a notably defined area can be found for craft specialisation, it tends toward professionality, which we can then infer a certain type of economic model for, which probably includes the workers having a certain type of public and private life. If they are primarily working out of their homes, we may be looking more at a kind of contractor type model.

Either way, what we’re seeing in the Classical Period is a great level of urban planning, primarily rooted in grid design. Cities will often place the Agora in the centre along with some kind of sanctuary that serves an ideological cult. Area for culture such as theatres or public assemblies may be placed in proximity to the Agora, but it is really the main streets that connect the districts where a lot of the main activities are taking place like shops & services. Naturally, the prime merchandise and storage will often come via the ports and coasts, which usually specialise in economic activity.

Sources

Alcock, S. 1993: Graecia Capta: the Landscapes of Roman Greece, pp. 1‑32, 33‑92, 93‑128, 172‑214

Robinson, D, Mylonas, G. 1929–1952. Excavations at Olynthus. In Johns Hopkins University studies in archaeology, no. 6, 9, 11–12, 18–20, 25–26, 31–32, 36, 38–39. 14 v. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press

Olynthus, vols. 1-14; J.W. Graham, Hesp. 22-23 (1953-54); Mabel Gude, History of Olynthus In Johns Hopkins Studies in Archaeology 17, 1933; Zahrnt 1971; N. Cahill, PhD diss. (UC Berkeley, 1991)

Camp, J. 2010: The Athenian agora. Site guide.

Osborne R. 2009: Urban landscape and architecture, in B. Graziosi, P. Vasunia and G. Boys-Stones (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Hellenic Studies, 239-247

Don't miss a post!

Sign up to get notified of when I upload as well as any new classes delivered to your inbox.

I hate SPAM. I will never sell your information, for any reason.