The Hellenistic Successor Kingdoms

Jul 15, 2024Following on from Classical Athens, it's time to move into the transition period leading up to the Hellenistic & Roman era of Greece. We should first call to mind that the term “Hellenisation” and “Hellenistic” are nomenclature that we coined, not so much terms that were found in Greece itself, at least in the same manner in which we use them. Historically, the Hellenistic period was sometimes seen as a time of decline for Greece, but I think it’s better to approach it as a kind of evolution and radical change. Throughout the period we will see trends of socio economic division, but also a continuation of themes that we already saw early on in the Archaic Period, mainly a decisive focus on the East & the influence of Turkey re-emerging, along with notions of Pan Hellenism & Greek identity.

Rather than a straightforward spread though, Pan Hellenism in this late period will be defined more as an interaction and merging between Aegean & Eastern cultures. In the same way as we saw in the Early Iron Age, Greek culture here has to be understood in relation to other cultures that it is interacting with. In a way, the Classical Period where we saw the rise of city states like Sparta & Athens is really more of a unique and exceptional time period where the influence of the East was lessened. There was never a uniformity to the adoption of Greek language and culture during the Hellenistic period, which naturally set the tone of the time as one of interaction, coexistence and sometimes, extensive conflict.

The Hellenistic Period

So, to begin, how do we even define the Hellenistic period? In older schools of Art History, “Hellenistic” was an art style defined by a decline in quality and sophistication in comparison to the Classical period. Sculpture does not seem to have had the same artistic value that it had in earlier periods. The challenge here is that this approach is entirely an opinion based on Western or later European aesthetic judgements. Look at any Hellenistic era sculpture and it’s easy to see more heavily defined emotive & humanistic themes, which a lot of people actually connect better with, in comparison to the idealism movements in early generations.

Looking at the archaeology tells a different story. Based on the age of people found in numerous Hellenistic era tombs, the life expectancy of the period actually seems to have been much higher, which usually we would associate with better standards of living. Hellenic domestic culture appears to have spread fairly rapidly throughout the known world, giving us insights into how prominent it was. This expansion naturally precluded a highly stratified sense of multiculturalism, which for many 19th century academics, was seen as a negative thing, diluting the perfection of Classical Greece.

In the modern view however, this multiculturalism was positive and allowed numerous cultures to come together and create powerful ideological, political and social dialogues that created a connected world very similar to our one today.

The “Hellenistic” period didn’t exist in antiquity, the time period was named in the 19th century from the Greek term hellenizo, meaning “I act Greek” to refer to the process of enculturation through which someone would speak and then eventually become Greek. “Hellenistes” was the term applied somewhat pejoratively to communities or ethnicities that “went Greek”, predominantly by speaking the language, and was chiefly applied to Jews in Jerusalem in the 160s BC. Naturally, this is not the best way to go about defining a culture. Culture is a lot more than just language, and the term Hellenistic creates an artificial sense of separation of Greek cultures from their neighbours or surrounding communities into which they were integrated.

To say that the Persian & Egyptian cultures were completely hellenised under Alexander just isn’t true. Instead we’re seeing a mixture of native elements from each culture interact with incoming Greek ideas, and those same ideas interacting and responding to native elements.

Philip II

Historically, we can begin talking about the cultural movement and spread that we call Hellenistic with Philip II of Macedon, or perhaps more specifically the major revolutions brought about by his conquering. While Philip’s campaigns certainly can be dubbed as political and expansionist, archaeologically the nuance is much more defined. A few posts ago I mentioned different ways in which Greek states identified themselves, not every one was a Polis. Macedonia, to the north, was instead a kind of Ethnos, an Ethnic State over and above a City State. The Ethnos state did not have cities in the same manner as other Greeks, but were inherently more mobile, with the occasional nexus of activity.

One such nexus was the now famous 6th century BC tumulus burials at Lofkend. Nestled in the area of the Mallakastra hills, which rise to the southeast of the modern regional centre of Fier, near the modern village of Lofkënd, it is at an altitude of 318 metres above sea level. The tumulus, which creates a significant shape dominating the local landscape, can be viewed from fairly substantial distances, and is located in one of the richest archaeological areas of Albania. Many of the burials in the Lofkend tumulus were done in succession over generations, and the area became a standard meeting place for funerary activities, which quickly doubled as an economic and political discussion zone, serving a similar role to a Polis.

As Philip began to take power though, he quickly moved towards models of governance and organisation that we are much more familiar with, namely the Polis plan systems. He founded a Polis at Pella that remained occupied from the late 5th century up until Roman times.

This Polis was fairly regular and had many of the same features we know from other ones, such as a grid plan system and an agora in the centre. Unlike other Greek Polises though, Pella had an enormous palace situated towards the top of the site, telling us a bit about the different kinds of social organisation going on. Clearly, as Philip & his administration began expanding and engaging colonies, they decided on the need for replication and copied a lot of the other political systems they were coming across in Southern Greece.

One of the places that we see this shift most strongly is the famous site of Vergina. This small town in Northern Greece is best known today as the location of ancient Aigai, the first capital of Macedon, complete with an extensive royal palace. In 1977, the burial sites of several kings of Macedon were uncovered here, including the tomb of Philip himself, which had not been disturbed or looted, unlike so many of the other tombs. Among the cluster thought to belong to Philip’s family, there are four monumental tombs, and a Heroon, a Greek Hero Shrine, likely dedicated to Philip’s family. A challenge we have though, is that we’re not entirely sure which tomb is Philip’s!

Opinion is split over whether he is interred in tomb I or II. There has been some substantial archaeological work done on the remains in both tombs, predominantly from an osteological approach. By examining the bones in tomb I for things such as arthritis and weakness of the knees or legs, we can get a picture of the kind of lifestyle the people had, including which activities they took part in. We know for instance that Philip was lame, which is consistent with the bones in tomb I.

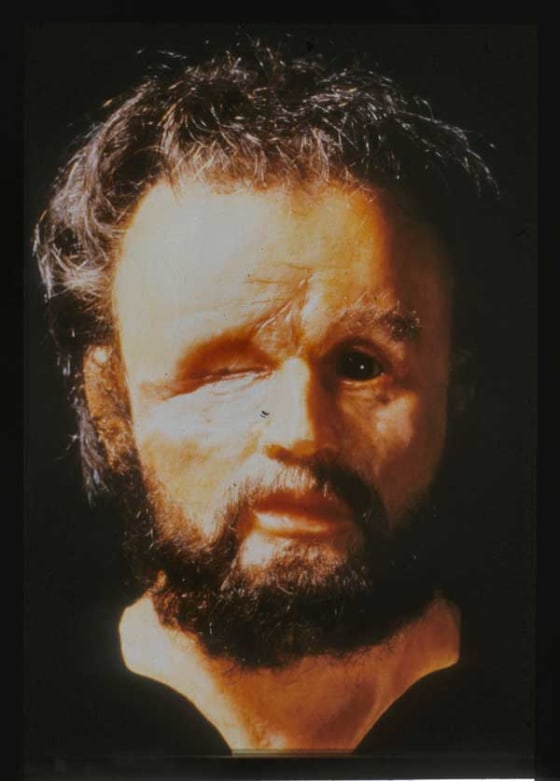

Alternatively, cranial reconstructions of the bones in tomb II coupled with comparisons to sculptures and busts of Philip have also yielded interesting results. Notably, evidence of a cranial injury to the skull in tomb II is consistent with literary records of Philip suffering an arrow wound to the right eye. Alongside these osteological arguments, material cultural debates centred around the kind of burial goods we could expect for Philip during the period have divided scholars. Unfortunately the debates for both sides are acrimonious, and no consensus is reached. In a way, it reminds me of the debates in Archaic archaeology around Homer. Even if we do prove Philip is one or the other, what have we actually learned about the past? What can knowing his final resting place do for our understanding of the Hellenistic period other than create a tourist attraction?

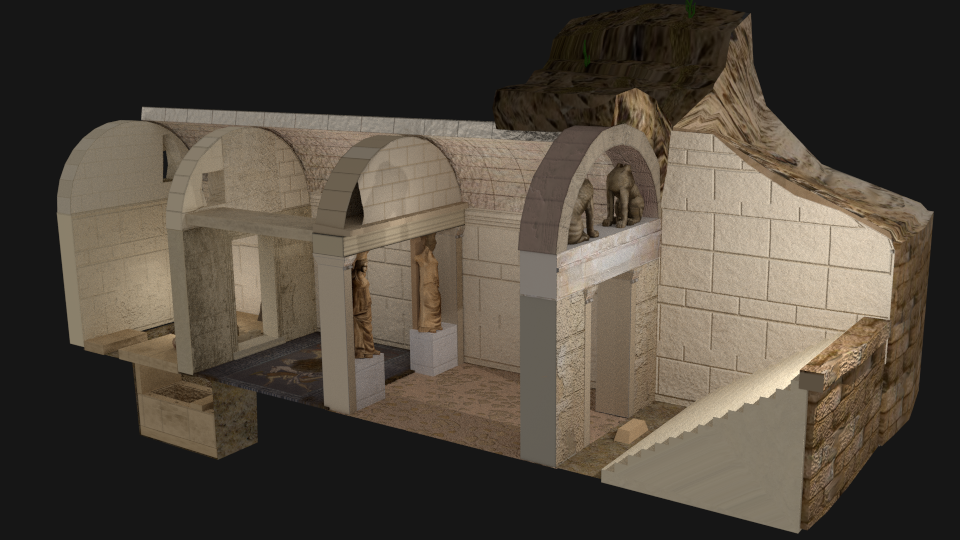

Well, if we set the identity of the tomb owners aside, there is actually a lot that can be gleaned from the burial goods! Here’s a schematic of tomb II, with the golden sarcophagus on the left. Interestingly, moving just outside the tomb to the threshold of the antechamber, there is another chest with another golden larnax which contained the bones of a woman wrapped in a golden-purple cloth with a golden diadem decorated with flowers and enamel, indicating a queen, who according to literary tradition would probably have sacrificed herself at the funeral. Remarkably, a lot of the materials associated with these human remains such as greaves, gorytos & alabastra, relate to warfare and military. These grave goods being associated with a woman signals that ideologies of power related to females during this period seem to be undergoing a shift.

Unfortunately though, further research into this topic is overshadowed by the focus on the identity of Philip.

Another greatly preserved site that we can look at to point to ideology in the Hellenistic period is the Kasta tomb of Amphipolis, not too far from Vergina. While we had known about Kasta for a while, and suspected that it was a Hellenistic artificial mound, the tomb was “re-discovered” in 2012 by Greek archaeologists and became a political sensation. In fact, this tomb’s tumulus is the largest ever discovered in Greece and by comparison dwarfs that of Philip’s. The first excavations at the mound in 1964 led to exposure of the perimeter wall, and further excavations in the 1970s uncovered many other ancient remains. The inner tomb was found in 2012 and eventually entered in August 2014.

Naturally, the monumentality and quality and artistic merit of the contents indicate it contained some very important people, but we’re still not entirely sure who. Around the time of its discovery, public speculation circulated that it was in fact the tomb of Alexander himself, which was quickly dismissed by the excavators, but it is nevertheless likely to have belonged to someone in Alexander’s close family or friendship group. In 2014, the remains of five people were found inside the lower levels of the third chamber. The bodies interred within were those of a woman likely older than 60, two men aged between 35–45, a newborn baby, and a fifth person consisting of only a few cremated bone fragments. Based on inscriptional evidence, the two dominant theories are that the Amphipolis tomb was dedicated either to Hephaiston, Alexander’s closest friend and confidant, or Olympia, his mother.

Either way, the sheer monumentality of these tombs is completely unlike anything we’re seeing in Athens or on the rest of the mainland, even the more well off people of Athens never had anything of this magnitude, which is a testament to Macedonia’s Heritage. This wider and more discernible difference between rich and poor is equally reflected in Pella that I mentioned earlier. As an example, we can look at the House of Dionysios there around 350 BC, clearly demarcated by size and complexity from other house types. This kind of stricter hierarchy and stratification is typical of what we would expect with a new territorial empire headed by a King. Here, we are very far from Democracy.

Alexander the Great

I’d be remiss of course, to speak of the Hellenistic Period without at least touching on Alexander. However, his exploits & life are largely the domain of history, not archaeology. Regardless, his efforts at unifying and spreading Hellenistic culture from as far afield as Egypt & India were unprecedented. A lot of work has focused on how exactly this newfound multiculturality fed back into and affected wider Greek culture. Following Alexander’s death, his empire was divided into provinces and administrative regions known as the Hellenistic Kingdoms, ruled mostly by his old generals. These kingdoms did not operate uniformly or have the same experience though.

In particular, the more heavily eastern kingdoms of Egypt & Babylon retained more of their indigenous culture in resistance to Greek occupation, whereas in other places we see much more a cultural mix with pronounced Hellenism.

Since these Hellenistic Kingdoms were inherently new states, their modus operandi was completely different to Classical Greek city states. To start with, they are inherently territorial states, not Polises, which created an entirely new class of politics and social structure. For instance, in such states we now have evidence of territorial monarchies, governing huge swathes of territory and diverse ethnic groups who were speaking multiple languages. The old Greek political system of a Polis cannot work for this, since while they are very good at organising local environments, they often struggled to maintain a relationship with a wider hinterland. Athens’ influence over its Chora was really an exception to the norm during the Classical period.

On the whole, the old power and political centres of Greece such as Athens and Sparta, during the Hellenistic period moved further east and south to places like Egypt & Anatolia, which became major empires. Economically and politically, these empires were the seats of power, although it could be argued that Athens retained cultural and ideological power during the Hellenistic period, especially in terms of Greek identity & literature.

A very common way to legitimise new rulers in these empires was through coinage. New coins were minted and put into circulation that contained iconography drawing on local motifs as well as older typically Greek icons such as the lion-skin cap of Herakles or the Eagle with the thunderbolt, and associated both with the faces of new kings to signal their divine attributes, in a similar fashion to modern political propaganda campaigns. Another primary way in which these rulers exert political influence is to take subtle inspiration from those Early Classical Tyrants, and build public architecture reflecting their power and prestige. A good example of this is the Panathinaikon Stadium in Athens.

This stadium had existed before, and even had a racetrack for horses as early as the 6th century BC, but in 140 BC Herodes of Atticus, the Athenian rhetorician, and Roman senator decided to rebuild it and clad it in pure marble. In the same vein, around 150 BC, the king of Pergamon, a region in Anatolia, built and renovated the Athenian Agora, notably building the Stoa Attalus. Why an Anatolian king would send money to a building project in Athens should tell you something about where the cultural and ideological power is in relation to the economic and political.

Looking toward his own kingdom, Pergamon is really one of the most magnificent developed states of the Hellenistic Period. The famous altar of Pergamon, now in the Berlin Museum, was originally located right next to the city palace, likely intended to signify the divine right to rule, and the ruler’s close personal connection with the gods. We can see clearly the differences of ideology and social power in these kinds of places by looking at the urban planning, architecture and house type. We are very far from the Tyrants of Athens now.

Sources

Stewart, A. 2008: The Persian and Carthaginian Invasions of 480 B.C.E. and the Beginning of the Classical Style: Part 1, the Stratigraphy, Chronology, and Significance of the Acropolis Deposits. American Journal of Archaeology, 112(3), 377–412

Bopearachchi, O. 2005: Contribution of Greeks to the Art and Culture of Bactria and India: New Archaeological Evidence. Indian Historical Review, 32(1), 103-125

Mairs, R. 2014. The Hellenistic Far East: Archaeology, language, and identity in Greek Central Asia. University of California Press

Prag, J. R. W. and Quinn, J. C. eds, 2013.The Hellenistic West: Rethinking the Ancient Mediterranean. Cambridge University Press.

UCLA Classics. 2007: The Lefkand Archaeological Project. Online. Available at: http://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/papadopoulos/lofkend/index.html

Grant, D 2020: The Royal Macedonian Tombs at Vergina. World History Encyclopedia. Online

Andronikos, 1976: Anaskafi sti Megali Toumpa tis Verginas. Archaiologica Analekta Athinon 9. 127–129

Chugg, A. 2018: The Occupancy of the Amphipolis Tomb. La Trobe University Seminar Series.

Chugg, A. 2021: The Identity of the Occupant of the Amphipolis Tomb Beneath the Kasta Mound. Macedonian Studies Journal. 2 (1)

Bartsiokas A, Arsuaga JL, Santos E, Algaba M, Gómez-Olivencia A. 2015: The lameness of King Philip II and Royal Tomb I at Vergina, Macedonia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

Bartsiokas A. 2000: The eye injury of King Philip II and the skeletal evidence from the royal tomb II at Vergina. Science.

Carney, E. 2017: Commemoration of a Royal Woman as a Warrior: The Burial in the Antechamber of Tomb II at Vergina. Syllecta Classica 27, 109-149

Salminen, E. 2017: The Tomb Doth Protest Too Much?: Constructed Identity in Tomb II at Vergina. In Theoretical Approaches to the Archaeology of Ancient Greece: Manipulating Material Culture, edited by Lisa C. Nevett, 273–94. University of Michigan Press

Ginouvès et al., 1992: La Macédoine, Paris

Stathopoulos, P. 2017: Did King Philip II of Ancient Macedonia Suffer a Zygomatico-Orbital Fracture? A Maxillofacial Surgeron’s Approach. Craniomaxillofacial trauma & reconstruction. 10(3), 183-187

Tsokas GN, Tsourlos PI, Kim J H, et al. 2018: ERT Imaging of the Interior of the Huge Tumulus of Kastas in Amphipolis (Northern Greece). Archaeological Prospection. 1-15.

Don't miss a post!

Sign up to get notified of when I upload as well as any new classes delivered to your inbox.

I hate SPAM. I will never sell your information, for any reason.