The Birth of the Greek Polis

Jun 24, 2024Following Homer’s works composed during the early Archaic Age, we begin moving towards social complexity. For the next few posts I will be focusing on the Archaic Age more generally, with a view to tracing the development of the Greek Polis. Roughly speaking we are dealing with the time period from 700 BC up to the end of the Archaic Period around 480 BC, marked by the invasion and destruction of Athens by the Persians. While this is the historical periodisation, basing the progression off this archaeologically is not ideal, and we will come to see, as socially and economically we see much longer lasting trends and overlaps between periods.

The majority of evidence during this period, including the cultural dynamics of the Polis, the primary urban socio-economical model in Ancient Greece, comes from Athens. While not ideal to only focus on one city, evidence for Polis states from places like Corinth or Sparta during this early period is not as well preserved. We do however have a decent amount of evidence from Crete for Archaic organisation, mostly as a by-product of the extensive work done there while studying the Bronze Age. I left off last time talking about the drastic changes we see exemplified from the 8th century onwards. Numerous demographic changes occurred, which we can see not only from new settlements arising all across the Aegean, but also by existing ones getting considerably bigger and more stratified.

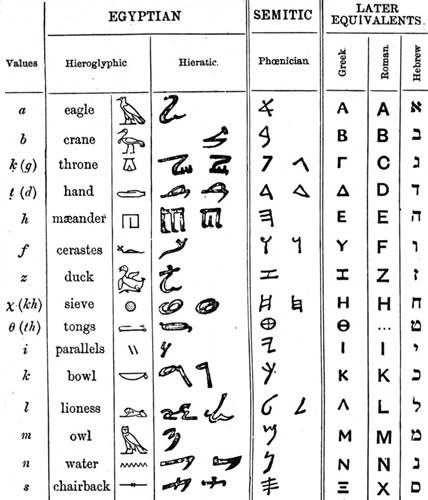

The small villages or hamlets that we saw during the Early Iron Age are beginning to amalgamate and come together under the influence of panhellenism, forming the early phases of what will eventually become places like Athens & Sparta. As a natural consequence of this, we can infer that beginning in the 8th century there was a noticeable population boom, indiciating wide economic growth, meaning societies had to adapt to new forms of social organisation to govern with stability. Culturally and artistically we see drastic changes to coincide with this such as new art styles depicting the human form as central as well as the introduction of the new Greek script from Phoneacian.

Unlike Mycenaean Linear B, some of the earliest inscriptions in Greek script are ideological or legal, usually centred around themes of identity such as who the carver is, their background or how things should be done. The famous Nestor cup I mentioned in a previous post is a good example of this. Its Homeric reference and potential use in an early form of Symposium among male elites signals the importance of Homer in defining Greek identity.

Despite this, from a material culture perspective, the early Archaic Period is much more heavily defined by its sense of regionalism. Despite popular thought about ancient Greece as a unified or homogenic culture, it has never been true that there is simply one single history of Greek culture.

While the Greek empire was briefly united under Alexander during the Hellenistic period, for the majority of its history, Greece was a loose but interconnected amalgamation of city states, all of which had their own culture, history & ethnic identity. During the Archaic period we have a much clearer understanding of how different these regional trajectories are. Primarily through seriation of pottery types, we can differentiate a few distinct cultures at play in the Archaic Aegean, most prominently the Proto Attic, typical of the area around Athens, Proto Corinthian around Corinth and outlying regions and the Eastern Aegean around Ionia. Each of these cultures had their own art style, iconography and motifs.

Eastern Aegean culture for example appears to have made use of wild goats in their iconography quite extensively. While there are certainly some overlaps in these cultures, many of them are equally exerting local differences. All regions use similar religious architecture in the form of sanctuaries for example, but exactly how a sanctuary shows up in any given place will be different. One of the driving forces for this regionalism has been argued to be an Orientalising influence that really defines the Archaic Period in general.

In the early Archaic, from around 720-600 BC we see a noticeable oriental influence being exerted on the Aegean, primarily in art and iconography clearly coming from the Levant, Mesopotamia and Egypt. This is of course nothing new, as intercultural connections between all of these regions were prominent during the LBA. The Archaic pithos depicting the Birth of Athena clearly takes inspiration from Mesopotamian cylinder seals depicting warrior goddesses such as the Akkadian Ishtar and the Ugaritic Anat. In the realm of Greek sculpture, the famous Kouros designs, depicting free-standing nude male youths clearly derive from Egyptian sculptural conventions and proportions.

This Eastern influence also penetrates areas of literature potentially even earlier, with some scholars noting similarities between Homer’s oral tradition and the Akkadian literary tradition centred around Gilgamesh. This influence appears almost ubiquitous throughout the Archaic period, but noticeably declines around the first half of the 5th century when, as a result of the Persian invasion, the concept of Greekness appears more fully defined and independent and actively seems to push away foreign influence.

The Development of the Polis

Influences aside, the major development during this period is that of the Polis, otherwise known as the Greek City State. The path to and eventual culmination of Athenian statehood and democracy was likely begun during the 8th century where we see clear evidence for the nucleation of settlements & villages. Now I will say, this is a challenging period to work with. How we define a Polis dramatically affects how we recognise and study one archaeologically. There are many different ways to approach thinking about a Polis, for example using textual or ideological definitions like that from Aristotle’s Politics. This is a fundamentally Emic approach, using the Greek’s own words to define themselves.

Aristotle defined the Polis as a self-sufficient and autonomous state, capable of making and enforcing its own laws. It would most usually have a central settlement known as the Asty & well as a surrounding hinterland or countryside known as the Chora which acted as its territory, both of which would maintain a strong connection with each other. The Chora would not have been large, but referred usually to the area immediately surrounding the central city that it relied on for subsistence. Aristotle also seems to apply that the ideal Polis would have a form of constitutional government, deciding how their laws would work. He traces its evolution from the komai (villages) in earlier periods, loosely organising together to form ethnē, confederations or ethnic groups.

This is considerably different to how we may define a Polis archaeologically however. Since Aristotle is essentially ideological, we need to rely on more physical metrics for understanding and recognising a city state in the material record. There is no magic population number that we can point to as a hard boundary, some self identified polises are very small, but nevertheless still operate as a state. Therefore, we are not so much looking places or communities as markers of statehood, but more so social relations and stratification. Based on things like burials and architectural differences we can infer differences of social class, implying cultural complexity.

Following on from the older Palatial systems, we may also expect to find monumentality present in a Polis, usually around that central village, most commonly related to identity, whether of the city itself or its prominent families. We can also look to the economy to define means of trade and subsistence. Evidence of specialisation for example can be a clear marker of a definable city state, coupled with understandings of who organises economic systems and how goods are distributed across the territory. We cannot really follow Aristotle’s definition of the Polis as being a result of Komai coming together, as occasionally we also find older urban centres being re-occupied and elevated to the status of statehood, sometimes by new inhabitants.

![1.3.15] Aristotle on the Political Structure of the City-State – Philosophy Models](https://philosophy-models.blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/aristotle-on-city-state-2.png)

Another challenge with defining and recognizing a Polis is that the Greek urban centres are somewhat unique in the ancient world. They do not always share traditional similarities with other well known urban centres from Egypt or Mesopotamia, so we must define the Greek city on its own terms. In comparison to Mesoamerican or Mesopotamian cities that often had four tier hierarchy systems for example, the Greek Polis often had a maximum of three classes, but most usually two, those living in the central city & those in the hinterland. It also rarely had expansive territory to draw from like we see from Egyptian Urban centres.

This makes comparing urbanism across regions difficult. We cannot use a “standard” checklist approach to see whether Greek Polises fit the typical urban model. On the other hand, we risk Hellenic Exceptionalism here. Believing that Greece is unique compared to other regions’ cities, which limits the degree to which we can use things going on in other places to help understand the process of Greek state formation. In later periods, we also find alternative forms of statehood in the North & North West of Greece such as the ethno-state that arises in Macedonia.

Macedonia did eventually become a city state later in its history under Philip & Alexander, but for much of its history, it was noticeably different from other Greek states. The Ethno-State of Macedonia was much looser both socially and spatially, organising themselves across landscapes rather than immediate surroundings. They do not appear to have had as rigidly defined hierarchies as the other Greek states, and occasionally Oligarchies arose. They also appear to define their identity very differently from the Hellenes, choosing instead to identify as a nation or spatially over and above political or state-based ethnicity.

The Archaeology

All of this naturally presents a challenge for archaeologists, most of all, how exactly we define and ultimately find an archaic city. While it may be tempting to believe that older cities were continuously occupied, this is one of the major problems. A lot of potential archaic cities are currently under modern inhabited towns. Like Troy, many Greek cities were continuously inhabited, meaning that later Hellenistic towns often overtook and built over the archaic cities of this period, oftentimes destroying the evidence. Given that many of the sites are still inhabited today, ethical & financial issues are often abound in modern Greek archaeology. Issues around publication & recording of finds are often paramount.

It’s not all doom and gloom though! A good example of a well studied Archaic period site is Knossos. The modern town of Heracleion is built over the top of the old Knossos village and is currently expanding relatively quickly. The Urban Landscape Project that I've mentioned previously has carried extensive work through almost all periods of Knossos’ habitation. During the archaic period, Knossos was again a huge town, roughly housing 30-40,000 people. While work is still ongoing to excavate and record this, encroachments from the modern city, both legally and illegally are wearing away at the evidence. All of this work is still currently going on, but naturally cannot be done in places like Athens due to its dense population.

Sources

Haggis, D.C., 2015: The archaeology of urbanisation: research design and the excavation of an Archaic Greek city on Crete. Classical Archaeology in Context: Theory and Practice in Excavation in the Greek World, pp.219-58

Whitley, J. 2019: The Re‐Emergence of Political Complexity. In I.S. Lemos and A. Kotsonas (eds.) A Companion to the Archaeology of Early Greece and the Mediterranean. Wiley, Chapter 2.3

Morris, I. 1991: The early polis as city and state in J. Price and A. Wallace-Hadrill (eds) City and country in the ancient world, 25-57

Polignac, F. de. 2005: Forms and Processes: some Thoughts on the Meaning of Urbanization in Early Archaic Greece in B. Cunliffe and R. Osborne (eds) Mediterranean Urbanization 800-600 BC, 45-69

Don't miss a post!

Sign up to get notified of when I upload as well as any new classes delivered to your inbox.

I hate SPAM. I will never sell your information, for any reason.