Religious & Cultural Reform in Roman Greece

Jul 19, 2024As the Hellenistic Successor Kingdoms spread, the encounter between Greek culture & Eastern indigenous populations informed a new cultural milieu. An excellent case study for the Hellenisation process is the site of Ai Khanoum, in Takhar Province, Afghanistan. The city was occupied from 280 BC and was likely founded by an early ruler of the Seleucid Empire and served as a military and economic centre for the rulers of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom until its destruction c. 145 BC. The city lay at the southwest corner of a plain in the region of Bactria, at the confluence of the Oxus (modern Amu Darya) and Kokcha rivers, and appears to have been heavily fortified.

It had all we would expect from a Greek colony, including a natural acropolis, around 60 metres high toward the east. Alongside this, a flourishing gymnasium and theatre occupied centralised spaces along with a temple and podium complete with an extensive propylaea and residential area. As well as these typical designs, we also have some things we might not expect. A monumental palace along with a mausoleum for one of the kings occupies a prominent place in the landscape, but even more interestingly, for part of the construction, they appear to have used brick as a material, which is exceptional, and in some ways very “un-Greek”, although it might better be explained by its location in Afghanistan, on the furthest edges of the known Greek world.

Its natural position between numerous rivers had the effect of setting it up as a kind of nexus point in the Bactrian region. The terrain in Afghanistan is notoriously difficult to navigate, and Ai Khanoum’s position made it a significant outpost and waystation for travellers through the region. This valuable position was not inherently Hellenistic however, it appears that Alexander simply took over pre-existing trade networks and local villages, adding in a layer of Greek culture over the top of local Afghani, raising questions of how exactly the local sites changed and to what extent.

Another key site to study the influence of Hellenisation is Nemrud Dagh, a 2,134-metre-high mountain sanctuary and tumulus in southeastern Turkey, notable for its summit where a number of large statues were erected around what is assumed to be a royal tomb from the 1st century BC. Like other Hellenistic tombs, Nemrud displays clear monumentality and pronounced visibility for the deceased king, Antiochus I of Commagene. His mountain top tomb-sanctuary is flanked by huge statues 8–9-metre high of himself, complete with two lions, two eagles, and various composite Greek and Iranian gods, such as Heracles-Artagnes-Ares, Zeus-Oromasdes, and Apollo-Mithras-Helios-Hermes. Of these deities, Heracles appears to have been incredibly popular among the Eastern Greek Kingdoms, perhaps because his myth lended itself well towards syncretism with other local hero cults.

When he was constructing this monumental pantheon, Antiochus drew heavily from Parthian and Armenian traditions in order to reinvigorate the religion of his ancestral dynasty. The statues appear to have once been seated, with the names of each god inscribed on them. At some point though, the heads of the statues were removed from their bodies, and they are now scattered throughout the site. The location of the site at the base of the Tigris & Euphrates rivers is clearly significant, and appears to occupy a strategic centre between Anatolia & the Aegean, which had been important since the Bronze Age.

The pattern of damage to the statues & heads (notably to noses) suggests that they were deliberately damaged, and the statues still have not been restored to their original places. The site also preserves stone slabs with bas-relief figures that are thought to have formed a large frieze. These stelae depict Antiochus' Greek and Persian ancestors, which are also found throughout the site. What’s really interesting about them is that they appear to have Greek-style faces, but Persian clothing and hair-styling, testifying to Antiochus’ desire to revive the Persian traditions of Commagene by merging the political and religious traditions of Cappadocia, Pontus, and Armenia.

Alongside these statues, the western terrace also contains a large slab with a lion, showing an arrangement of stars and the planets Jupiter, Mercury, and Mars in the form of a chart of the sky dated to the 7th July 62 BCE This may be an indication of when construction began on this monument.

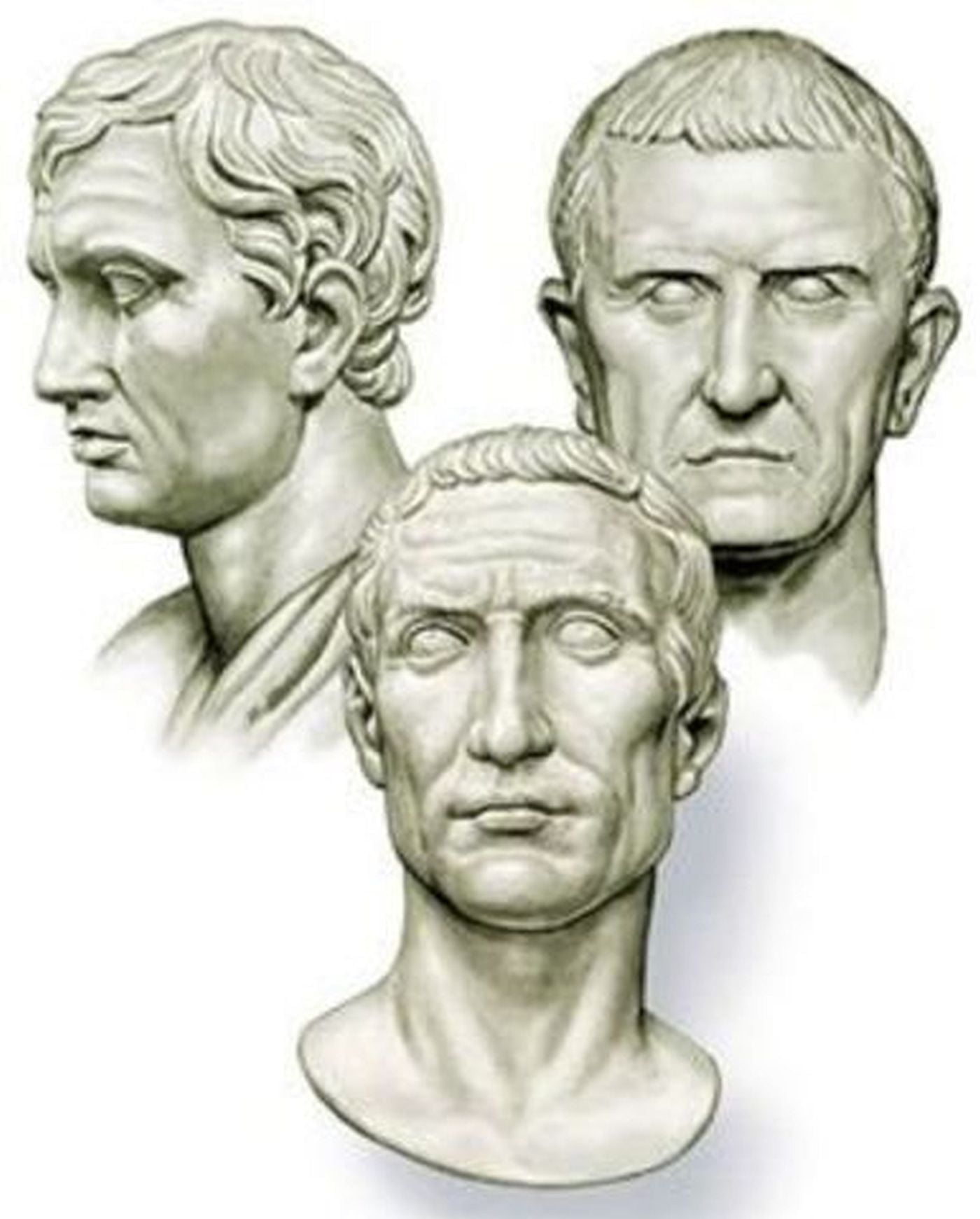

The Romans

As time marched along in the Hellenistic world, the rising superpower of the Romans began to take notice. The history of Roman occupation of Greece however, spans nearly 200 years of continued effort on their part of trying to get Greece under Imperial control, along with at least 3 wars. Beginning around the 200s BC, the 2nd Macedonian War marked Rome’s victory and influence over the Balkans, and while there doesn’t seem to have been any formal military occupation, Rome did begin intervening in Greek political affairs. This influence culminated in the 3rd Macedonian War between 172 and 168 BC, in which the Greek city state of Corinth was sacked, bringing the region under Roman control.

The final transition to Imperial Control however, was accomplished in the context of the civil wars of Pompey, Caesar, Octavian and Antony, notably in the final battle of Actium off the coast of Epirus in 31 BC, in which Octactian defeated Antony & Cleopatra. Following this, Greece became an official Roman Province under the name of Achaia, however, Crete Macedonia and Thessaly were not counted as part of this administrative region. Later on, even Epirus was made into a distinct province.

As may be expected for such a turbulent period, archaeologically we see great amounts of evidence for warfare and social disruption in the form of land tenure and agricultural production.

Along with the extensive movement of outsiders such as colonists and foreign army veterans into Greece, we equally see administrative records of land confiscations increasing and notable rises in public and private debt, putting special strain on local economies, which localised elite families attempt to cement their influence in.

Geographically and politically, we have a wide ranging distribution of newly administered cities and leagues, each of which now had different statuses, legal roles and titles in the new government. This radically changed the importance and influence of certain historical cities. On Crete for instance, Knossos was the historical capital and administrative centre in the Hellenic and Hellenistic period. When the Romans invaded, Knossos mounted a resistance against them. In retaliation, when Rome finally cemented its rule, the Imperial Administration took the title of capital away from Knossos and moved it to the south in Gortina, which naturally triggered the decline of the once great city. On the whole, these Polises were now defined by the title or legal role they were given by Rome.

Following archaeological surveying data, we also see substantial evidence for settlement pattern change in the Roman Period. On the whole, settlements became much more centralised, with the growth of large estates creating a dissolution of small land ownership. Equally, Roman landlords appear to have had a tendency to increase the separation they had with their land. They would rarely live on the estate itself, but rather in the major cities, ensuring to build larger villas or elite residences to remind locals of who was really in charge. This naturally created an increasing nucleation in larger rural communities following the abandonment of isolated farmsteads. For a brief period of time in the Late Roman era, this trend appeared to wane and local officials tried to re-extend their influence, perhaps out of fears of losing control.

Under Emperor Hadrian however, is when Urban transformation truly got underway. Founder of the league of Greek city-states known as the Panhellenion, Hadrian was philhellene and idealised the Classical past of Greece. The league was set up, with Athens at the centre, to try to recreate the apparent "unified Greece'' of the 5th century BC, when the Greeks took on the Persian enemy. It was primarily a religious organisation, and most of the deeds of the institution which we have relate to its own self-governing. Admission to the Panhellenion was subject to the scrutiny of a city's Hellenic descent. As part of his work, Hadrian extensively re-developed and modernised Athens. He ended up renewing many of the Polises and rebuilding many public buildings such as the baths and theatres along with a newly modelled agora.

Interestingly, even though Hadrian admired Athens’ past, he doesn’t seem to have renovated the Tholos or the political monuments related to the 50 tribes, instead choosing to focus on economic or public interest buildings such as the Odeon or various temples. His focus was on art and performance over and above politics. We can account for this as many of the high level political decisions were no longer taking place in the agora, but back in Rome or in the offices of local governors.

Arguably the most important benefit the Romans brought to Greece though were the roads. Roman roads were and still are infamous for their economic and inter-regional connection that brought extensive economic development. But an often unspoken part of Roman occupation was the change they brought to religious expression. In Classical Polises, the city would often have a local temple, usually associated with their own political ideology as well as controlling the hinterland around them with smaller temples to create a cultic landscape. During the Roman period however, this theme declined in favour of the Imperial Cult. What once were local cults became increasingly appropriated by the cult of the emperor, reflected in an increasing number of Roman statues and busts of the rulers. While local and rural cults did not disappear entirely, they significantly declined in activity.

Augustus for example, appears to have engaged in quite an extensive campaign of religious restructuring, with statues and altars of his own Imperial Cult appearing all across Achaia. He put one in nearly every major site in Greece.

This kind of hybridisation was not just felt on the religious, but political level too. One final good example of this is the famous Philopappos monument still standing in Athens today, right outside the Acropolis. Philopappos was not originally Athenian, which by Classical Period standards would have excluded him from having any kind of political or monumental representation in the city, but in his own Roman Period lifetime, he was afforded a huge political monument right in the centre of the precinct area. Unlike the earlier Keramikos tombs in which social differentiation was often lessened, the Philopappos monument is visible for miles around the Athenian countryside. This is clearly a very different way of self-identification, especially in establishing tombs as a means of control to show populations where the true power lies.

Sources

Alcock, S. 1993: Graecia Capta: the Landscapes of Roman Greece, pp. 1‑32, 33‑92, 93‑128, 172‑214

Alcock, S. 1997: Greece: a landscape of resistance? In D. J. Mattingly (ed.) Dialogues in Roman imperialism : power, discourse, and discrepant experience in the Roman Empire, 103-115

Bopearachchi, O. 2005: Contribution of Greeks to the Art and Culture of Bactria and India: New Archaeological Evidence. Indian Historical Review, 32(1), 103-125.

Martin-Mcauliffe, S. L. and J. K. Papadopoulos. 2012: Framing Victory: Salamis, the Athenian Acropolis, and the Agora. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 71(3): 332-361.

Erskine, A. 2003: A companion to the Hellenistic world (Blackwell companions to the ancient world. Ancient history). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing

Leriche, P. 2007: Bactria, Land of a Thousand Cities. In Cribb, J; Herrmann, Georgina (eds.). After Alexander: Central Asia Before Islam. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lerner, J. 2010: Revising the Chronologies of the Hellenistic Colonies of Samarkand-Marakanda (Afrasiab II-III) and Aï Khanoum (Northeastern Afghanistan). Anabasis: Studia Classica et Orientalia (1): 58–79

Goell, T. 1957: The Excavation of the "Hierothesion" of Antiochus I of Commagene on Nemrud Dagh (1953-1956). Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. The University of Chicago Press. 147: 4–22

Brijder, H A.G., ed. 2014: Nemrud Dağı: Recent archaeological research and conservation activities in the tomb sanctuary on Mount Nemrud. Boston, MA / Berlin, DE: Walter de Gruyter

Boatwright, M T. 2003: Hadrian and the Cities of the Roman Empire. Princeton University Press,

Martinez-Sève, Laurianne. 2014: The Spatial Organization of Ai Khanoum, a Greek City in Afghanistan.. American Journal of Archaeology 118 (2): 269

Andreeva, P. 2018: Fantastic Beasts Of The Eurasian Steppes: Toward A Revisionist Approach To Animal-Style Art. PhD Thesis, Parsons School of Design.

Mourtzas, N, Kolaiti, E. 2017: Geoarchaeology of the Roman harbour of Ierapetra (SE Crete, Greece). Géoarchéologie du port romain d’Ierapetra (Crète sud‑orientale, Grèce)

Don't miss a post!

Sign up to get notified of when I upload as well as any new classes delivered to your inbox.

I hate SPAM. I will never sell your information, for any reason.