Power, Equality & Social Mobility in the Greek World

Sep 02, 2024The changing nature of power in the Greek world has been a major point of discussion, especially in recent years. Athenian statehood & political identity has obvious ramifications for how we understand the very nature of a Democratic system, even today. The 19th century belief in progress, although shaken in the 20th century, continues to dominate Euro American popular culture. At a very young age, we are socialised to think that societies evolve inevitably toward the Euro American political and economic institutions of today. Where this fails to happen, our government formulates foreign policies to help the process along. We treat the cases where evolution to greater complexity is punctuated by collapse as aberrations and catastrophes that do not negate the trend. In 1914, European powers and their offshoots controlled 84 percent of the earth’s surface, and their undoubted military prowess cemented the evolutionary presumptions.

In these next few posts I'm going to be looking at the ways in which the Greeks defined their relationship to power, especially in how different societal groups were represented and found expression for their voice and identity. I want to mostly look chronologically, but there will naturally be some time periods where ideas overlap & I’ll tend to focus more thematically there. As part of this focus, I want to also explore the idea of warfare from the Archaic period onwards to better define what we mean by power.

I’d like to start this by posing a question for us. How do you think we would interpret Athens without textual sources? We have extensive remains to study, sure, but what would our picture of Athens (and Democracy for that matter) look like without texts? What would we think about the nature and organisation of the city & its relationship with its hinterland? Naturally, we have the Agora, which would be difficult to define meaningfully since it is so multifunctional as a space. Maybe we could point to the Acropolis as a symbol of identity because it dominates that space, has better preserved buildings & a much clearer sense of restriction and hierarchy, but even then, it was never the house of a ruler. It was a temple.

What about the Pnyx? The space on the corner with two late Stoas. Can we say that was a political space or an educational and public one? Zooming out, how can we understand the relationship between all of these spaces and their architecture? How can we really understand things like wealth, structure & power from what we have in the material record?

The bulk of a farming population generated an archaeological record so minimal that we have either not detected or not recognized it. With some obvious exceptions, such as when lithic debris or broken pottery is deposited or when people live in an aggregated community, people throughout most of human existence have had little capacity to generate a salient archaeological record. Prior to the industrial era, most people simply did not produce, possess, or deposit enough durable material culture to do so.

Our story of power therefore needs to start earlier. Houses or domestic buildings are often a good place to start when examining class divides. Architectural style and grouping certain motifs such as sophistication, room type & space and other factors often make good quantitative measurements to establish class differences. Some houses are larger, some smaller and some, over the course of habitation become larger and the inhabitants gain more social standing or resources. Such quantitative measurements can inform qualitative ones about people’s social standing & relationship with each other.

In the same vein, looking at things like burials & grave goods are always useful. The most salient archaeological record many people are able to generate is their own corpse. It is no coincidence that archaeologists studying so-called dark ages, like post-Mycenaean Greece or post-Roman Europe, have tended disproportionately to concentrate on burials, for often those are the only archaeological record that they can find. On the other side of it, though, to focus as we do so predominantly on salient remains is thus to disenfranchise much of humanity.

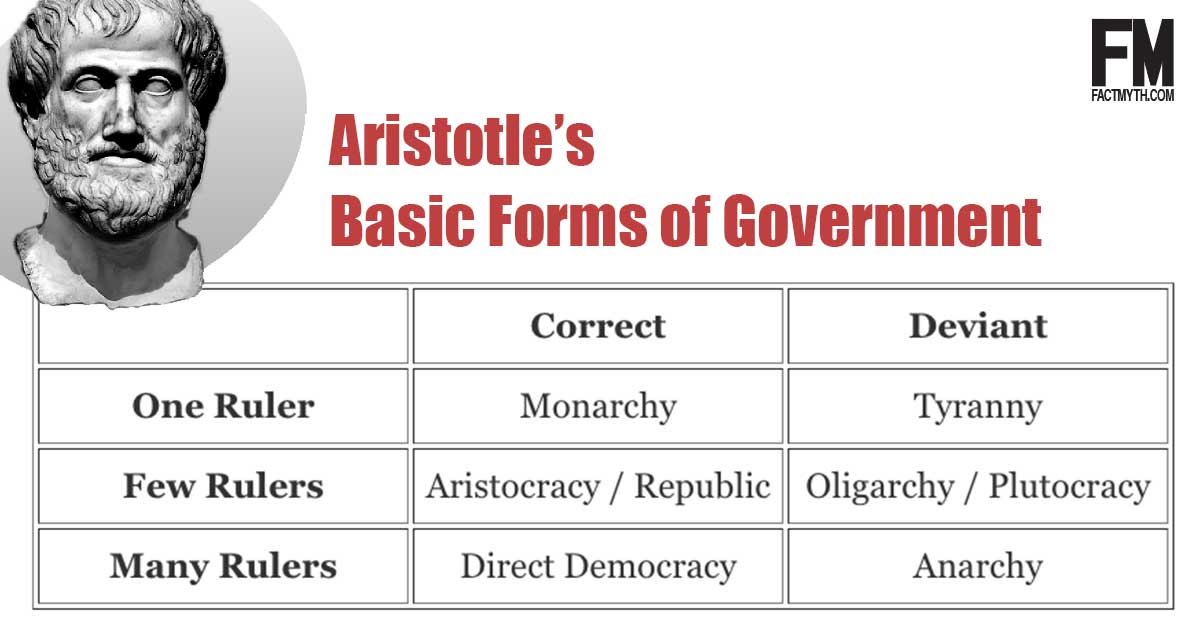

While burial typology may be similar, examining things like quality of goods, the original provenance of such things & quantity, we can infer ideas about a person’s class & social mobility. The Greeks had a clearly defined vocabulary around types of rulership, many of which have come down to us. Remember the following terms: Oligarchy, meaning a rule of the few, usually aristocratic families, Aristocracy, defined as a rule of the best, Plutocracy, meaning a rule of the rich and wealthy, Monarchy meaning rule of one, Tyranny meaning a rule of one who has acquired power through non monarchical definitions, Meritocracy meaning a rule granted to ones who earn it and Democracy meaning a rule by the popular people.

Chronologically we can chart the general evolution of Greek power structures from the Mycenaean period up to the Hellenistic. During the Mycenaean period, rulership and direction was orchestrated by a Wanax. This model influenced the local communities of the Early Iron Age to become headed by figures comparable to chiefs. Throughout the Archaic period, power systems shifted dramatically & constantly, with small scale communities going through periods of Tyranny, Oligarchy & Monarchy before culminating in Athenian Democracy, which became the default standard for power sharing during the Classical period. As we head into the Hellenistic & Roman periods though, the model clearly shifted back to an Oligarchic Monarchy.

Now, of course, this chronology does not work for all sites, in fact it actually works for very few, because it's so Athenian centric. Not only does it present previous periods as deficient, ultimately culminating in a golden age of Athenian democracy, it also subtly presents the later Hellenistic & Roman periods as deficient or in decline in comparison. If we move north to Macedon or south to Crete, the organisation and dynamics of power shift pretty dramatically.

Understanding that Athens is really more of a unique case study than the standard model of power in the Greek world is vital to truly representing other systems. If we were to think thematically across periods, we can talk about them as being defined by the dialogues of power between different aspects of society. The Aristoi, or elites, on the one hand and Free Men on the other. In certain scenarios, it works to view things as a top down effect in which there is a well defined circle of power makers and enforcers, but in others -especially democracy, this circle is actively created through community wide cooperation. How these different natures of power are expressed, mediated, directed, and at times stretched beyond their breaking point is necessary to think about and better define.

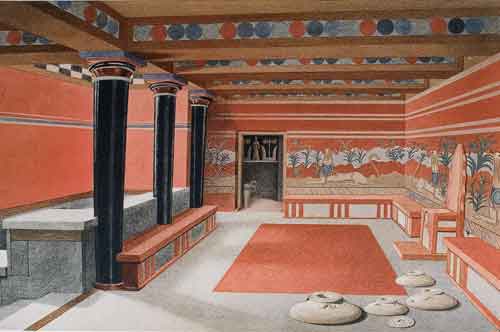

As a case study, let’s look at Minoan Crete. As I mentioned at the start of this series, despite the sophistication, we have no evidence for rulers here. Despite this, we have substantial evidence of well developed urban centres and palaces, which clearly someone, somehow must be organising. There are equally some traces of house style differentiation indicating some degree of class difference. If we look at palaces like Malia and Knossos, our focus would naturally be around the central spaces and western courts that seem to indicate efforts to attract people through defined sophistication like artwork and artisan production. While there’s clear evidence of religious practice, there is little in the way of a single ruler.

At smaller sites like Gournia, the palace-style building was fit into the already existing town, perhaps to emulate one of the bigger centres, maybe because local residents were involved at an event there and wanted to create their own interpretation. This would imply a bottom-up model of power in which local communities can exert their own influence. If we go to Knossos, we naturally have the throne room, but this is actually quite late and likely not even Minoan. The palace had already existed for nearly 200 years before they decided on the need for a throne. Equally, we don’t know the kind of power dynamic that the occupant of this room may have had. We talk about a “ruler”, but the individual could just have easily been a religious or economic official rather than a king or queen.

This ambiguity around Cretan power is also a challenge in Minoan iconography. If we look at Egypt or Mesopotamia, signet and cylinder seals show clearly defined hierarchical figures. On Crete, it’s surprisingly difficult to establish any certainty around iconography and who is being represented. One exception to this is the so-called Master Seal from Chania, dating to the Late Minoan Period, which depicts a figure towering over a city. Opinion is split over whether this figure is a military or communal leader, clearly emulating the Sumerian monarchal image of the Good Shepherd, or whether it is a deity. On other seals, we see women in the same pose and with the same staff.

One popular theory is that while men may have controlled the political and military sphere, women may have had a more significant role in the religious one, as -in general, priestess or deity iconography, especially those engaged in ritual are commonly more feminine.

As we move into the Mycenaean period, defined boundaries become much clearer.

The palaces are clearly organised and centralised around a megaron throne room, occupied by a Wanax. Despite this, the Wanax was not all powerful in the sense of a mediaeval monarchy though, with a proliferation of religious and economic roles being filled by other administrators. Mycenaean culture also has a markedly more pronounced emphasis on monumental tombs, serving not only as economic and ideological goals but also as statements in the landscape, which equally implies descendants are still in power.

As we move into the Early Iron Age, looking at Knossos becomes even more interesting. Even in the period after the collapse of the palace we do still have evidence that the community existed there, primarily through the emergence of cemeteries. Some of these EIA tombs have long dromos’, or entrances, which clearly would have required immense effort. By examining imports that served as grave goods though, we can see a clear differentiation, with some tombs having up to 10 or more foreign vessels, while others have as little as 1. Some of the tombs even seem to be aligned to each other, perhaps indicating familial relationships.

When reading texts to inform our understanding of power, we have to be careful of defining which period and form of Greek we’re working with. Alongside the Wanax in Linear B, we have evidence of another title for rulers, a qa-si-re-u, who appears to be a kind of local community chief under the power of the Wanax. This term, qa si re u becomes Basileus in Archaic Greek, but changes to denote a sovereign. By the time we get to Athens, Basileus is not being used to denote a traditional king, but more of a magistrate. It’s only Alexander during the Hellenistic period that uses the term to denote fully fledged kingship.

It is nevertheless interesting to observe the evolution of the Basileus from a local ruler to a sovereign. Perhaps as the regional Wanax disappeared following the collapse of the palatial economy, those local chiefs centralised their own power and grew in importance. As we move into the 7th and 6th centuries, the local Basileus grew into Tyranny, again not originally a pejorative term until the advent of Democracy. The rise of Tyranny is to be considered another phase in the transformation of power, one that built upon the expansion the Middle Class experienced during the Archaic Period. Tyranny therefore becomes a means of dialogue between members of society such as artisans, military commanders and hoplites and the aristocracy. The foundation of a Tyrant’s power is their ability to sustain links with the Middle Class and acquire favour from them.

Following Solon’s property class reforms of during the early 6th century, we see a small-scale transition toward a timocracy, in which social standing is now determined by wealth and property ownership rather than aristocratic background. Again, this can be conceptualised as a means by which the Middle Class is asserting its political and ideological identity. Your ability to hold office being determined by your acquisition of property opens the game for other members of society to hold political influence and arguably anticipates democracy.

All of these changes and transformations in such a small window of time indicates just how fragile power as a structure really is.

It’s therefore no coincidence that it is around the same time in the 7th and 6th century that we start to see the first Law Decrees being written in an attempt to curb the acquisition of power. In the case of Tyrants, they often acquired such power by directly benefiting the Middle Class, usually through the construction of infrastructure or civic projects.

Following the events of the Tyrannicides, Cleisthenes radically reformed Athenian society to make sure that power was distributed evenly and no one group could acquire disproportionate influence. His division of districts into Men of the City, Shore and Interior as an organisational system for the 10 tribes became the basis of future political organisation

Sources

Ober, J. 2017. Mass and elite revisited. In Evans, R. (ed.) Mass and Elite in the Greek and Roman Worlds: From Spart to Late Antiquity. London: Routledge, 1-10.

Hall, J. 2010. Autochthonous Autocrats: The tyranny of the Athenian democracy, in Turner, A. J., Kim Chong-Gossard, J. H. and Vervaert, F. (eds). Private and public lies: the discourse of despotism and deceit in the Graeco-Roman world

Morris, I. 1991 The early polis as city and state in J. Price and A. Wallace-Hadrill (eds) City and country in the ancient world, 25-57

Ober, J. 1989. Mass and Elite in Democratic Athens: Rethoric, Ideology, and the Power of the People. Princeton.

Van Wees H. 2002 Megara’s mafiosi: timocracy and violence in Theognis, in R. Brock and S. Hodkinson (eds) Alternatives to Athens: varieties of political organization and community in ancient Greece

Pollard, D. 2021: All equal in the presence of death? A quantitative analysis of the Early Iron Age cemeteries of Knossos, Crete, Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, Volume 63

Eaby, M. 2007: Mortuary Variability in Early Iron Age Cretan Burials. Dissertation University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Don't miss a post!

Sign up to get notified of when I upload as well as any new classes delivered to your inbox.

I hate SPAM. I will never sell your information, for any reason.