Hoplite Warfare and the Aristocratic Class

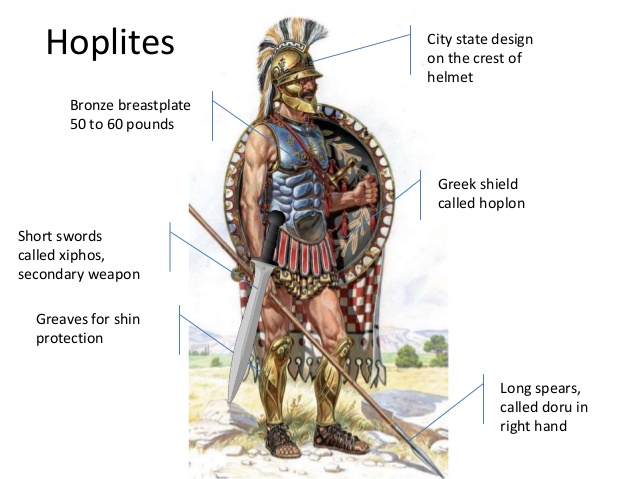

Sep 06, 2024In any discussion of Greek exchanges of power, warfare and strategy, you will inevitably encounter the infamous citizen-soldiers of the city-states, known as the Hoplites. These warriors pose a unique way of fighting for us, one which is reliant on few numbers but nevertheless effective. Through the use of phalanx formations they were discouraged from acting alone, as this would compromise the formation and minimise its strengths. While usually only considered in the context of the military, Hoplites were dependent on specific armour, shield and spear equipment that could usually only be afforded by the Middle or Artisanal Classes, and therefore equally served an economic and social role in Greek society.

They were primarily represented by free citizens –that is, propertied farmers and artisans, therefore most hoplites were not professional soldiers and often lacked formal military training. In a way, they are the idealised fighting force suited to a democracy. Primarily defined by shield and spear combat, the practicalities of Hoplite warfare are interesting to look at. The phalanx formation advanced units as a cohesive whole rather than individuals, akin to a modern rugby scrum. We can think of an individual hoplite soldier as having a “weak side”, in which they held their weapon and therefore were less defended compared to their shield in the other hand. They often got around this by standing closer to other soldiers so that the next shield in the line would overlap with the individual’s exposed side.

In this sense, you had to rely on comrades for part of your defence, which would have been enshrined in the sense of community. Now, anyone familiar with terrain or the battle of thermopylae will know that phalanx formations are actually pretty difficult to set up properly; there are only a limited number of terrains and environments in which it is effective. Many Greek battles relied on being “set up” properly, having the right environmental conditions and flat terrain, which meant pronounced weaknesses against certain weapon types or notably, cavalry. Ironically, this style of warfare worked in regions around Thebes or Attica where the land was flatter, but struggled in the Penepolese. While certainly ideologically effective at reinforcing state principles, the military applications can sometimes be questionable.

Literary testimonies to such battle conditions or the ineffectiveness of hoplite phalanxes are numerous. Strabo (10.1.2) claims to have seen an inscribed pillar from an agon between Calchis and Eretria in the late 8 century that had conditions of warfare inscribed on it, including the agreement between parties not to use missiles. Herodotus (7) equally reports that the Persian Mardonius ridiculed the Greek way of fighting on only the best and most level ground. In his first book, Herodotus also references a fascinating event in which an agreement between armies took place:

“The Argives came out to save their territory from being cut off, then after debate the two armies agreed that three hundred of each side should fight, and whichever party won would possess the land. The rest of each army was to go away to its own country and not be present at the battle, since, if the armies remained on the field, the men of either party might render assistance to their comrades if they saw them losing”

This inevitably makes us question the nature of warfare and rules of engagement in the Greek world. The other downside of hoplite warfare is that your soldiers are in fact the same citizens who are producing goods and fueling your economy. Big battles or drawn out wars that take such people away from their properties for extended periods of time inevitably had consequences for food and production that few cities could sustain long term. In this line of thinking, people have frequently looked at hoplites as indicative of social change. Having a hoplite army not only requires the money or grain to upkeep them, but also offers the free-citizens of Athens, what we would call the Middle Class today, the opportunity to mobilise.

Different scholars have examined this power dynamic in different ways. The late John Salmon discussed hoplites arising from the perspective of political discontent among non-aristocratic families in the context of the tyrant revolution in the archaic period. In the late 90s, Victor Davis Hanson re-focused the debate around agricultural revolutions, arguing that first what was needed was a change in how farming and food production occurred on a mass scale. In order to sustain a hoplite economy, aristocratic control of farmland had to give way to a network of interconnected farming estates that could maintain production of weapons and rations.

In the early 2000s, Hans Van Weese went the other way, arguing that hoplite tactics were never static, and that methods of battle continually evolved through a slow progression and refinement of strategy, and therefore hoplite warfare was a consequence, not the cause of political change. In other words, while Salmon and Hanson believed that changes and developments in hoplite warfare pushed state ideologies toward cooperation and democracy, Van Weese believes that democracy was the ideological and state background that created hoplite evolution. A lot of the current debate lies in situating such developments in time, especially whether hoplite warfare precedes or proceeds evidence of democracy.

It’s worth considering the role of colonisation in the formation of hoplite identity and power dynamics too. Developments in phalanx strategies seem to coincide with developments and expansions of Greek colonisation. As areas at the far reaches of the Greek world, such colonies are the avant garde of society in which great change occurs, often through cultural interaction. While texts often tell us that such colonies were founded by aristocrats, the archaeology doesn’t always reflect this. Instead, it seems more like colonisation is an arena in which radical social and political change occurs and sometimes even feeds back into mainland society. The question that needs to be asked is how much of free-citizen colonisation is breaking aristocratic control, and what does that new dynamic look like?

Especially if we look at the colonies in Magna Graecia, we are seeing evidence of new models of land ownership, agricultural development and even trade, which allows for cheaper metal sources and a wider variety of not only typology, but also who is using such weapons.

There is a fair amount of archaeology focused around battlefields, especially recently in places like Himera, Sicily. We think this may be evidence of the Battle of Himera around 480 BC, fought on the same day as the Battle of Salamis, or at the same time as the Battle of Thermopylae. This battle saw the Greek forces of Gelon, King of Syracuse, and Theron, tyrant of Agrigentum, defeat the Carthaginian force of Hamilcar, ending a Carthaginian bid to restore the deposed tyrant of Himera. The discovery of mass lined graves in 2007 & 8 seems to confirm the location and historical existence of this conflict.

In the mass graves, some skeletons have evidence of their hands being tied, along with spearheads in their shoulders, which may suggest execution after such a conflict. More so than the battle itself, isotopic analysis of the bones is turning up interesting data about the ethnicity of those buried there. Such DNA analysis is helping us identify whether these soldiers are local people or mercenaries paid from abroad. Such analyses can tell us more about the nature of warfare, but also about the internationality of conflict.

In the same vein, there are discussions about how iconography can contribute to our understanding, especially with things like the Chigi Vase from Italy. This 7th century vase depicts hoplites in conflict accompanied by a young boy playing what seems to be an aulos flute, perhaps to provide the phalanx with marching rhythm.

Interestingly though, on the layer below this we have figures in the same style of armour on horseback, acting seemingly as cavalry, which goes against standard hoplite tactics.

We equally have quite a wide distribution of votive offerings resembling hoplites at religious sanctuaries, especially in 5th/6th century Sparta and wider Lakonia, particularly around the Menelaion. This act of votive deposition is perhaps reflecting wider religious changes in Greek society that reflect changes in hoplite importance, organisation and value.

Sources

Foxhall, L. 2013. Can we see the ‘hoplite revolution’ on the ground? Archaeological landscapes ,material culture and social status in early Greece in Kagan, D. and Viggiano, G. F. Men of Bronze. Hoplite warfare in Ancient Greece. Princeton University Press. 194-221.

Hanson, V. 2000. Hoplite battle as ancient Greek warfare. When, where and why? in H. van Wees (ed.) War and violence in ancient Greece, 201-232

Ober, J. 1989. Mass and Elite in Democratic Athens: Rethoric, Ideology, and the Power of the People. Princeton.

Schwartz, A. 2002. "The early hoplite phalanx; order or disarray", Classica et Mediaevalia 53, 31-64 (TC 3166)Snodgrass, A. M. 1999. Arms and Armour of the Greeks

Van Wees, H. 2004, Greek Warfare, Myths & Realities. Bristol Classical Press

Whitley, J. 2001. The Archaeology of Ancient Greece. Chapters 8, 13. Cambridge University Press

Krentz, P. 2002: Fighting by the rules: The invention of the hoplite agôn. Hesperia. 71 (1): 23–39

Kagan, D; Viggiano, G. 2013: Men of Bronze: Hoplite warfare in ancient Greece. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press

Herodotus. 1996: Herodotus: the Histories. London, England; New York: Penguin Books

Crowley, J. 2012: The Psychology of the Athenian Hoplite: The culture of combat in classical Athens (hardcover ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Reitsema, L, Mittnik, A, Kyle, B, Reich D, et al. 2022: The diverse genetic origins of a Classical period Greek army. PNAS vol. 119 | no. 41.

Freeman, E. 1891: The History of Sicily from the Earliest Times, Volume 1 PCMI collection The History of Sicily from the Earliest Times. Clarendon Press

Don't miss a post!

Sign up to get notified of when I upload as well as any new classes delivered to your inbox.

I hate SPAM. I will never sell your information, for any reason.