Can We Trust Homer as a Historical Source?

Jun 17, 2024Arguably the most well known aspect of Ancient Greek culture, especially that of the Bronze to Iron Age transition is the story of Troy. For centuries, the Iliad and the Odyssey, attributed to the legendary poet Homer, have captivated us with their tales of valour, wrath, and heroes. Yet, the existence of a real Troy, the battleground of the Trojan War, has remained shrouded in mystery, almost always blurring the lines between legend and historical fact. It wasn't until the late 19th century that the quest to uncover the physical remnants of Troy became a reality. The pioneering excavations by Heinrich Schliemann brought the city onto the archaeological agenda, revealing layers of history and sparking debates that continue to this day.

![]()

The allure of Troy extends far beyond its archaeological footprint. It is a testament to the enduring power of storytelling and its capacity to embed itself within the fabric of history. Homer's epics, with their rich tapestry of gods, heroes, and monsters, continue to echo through us, inspiring countless generations because at their heart, it is just a good story. It’s THE story. In the words of Aristotle, Homer was “the Man who taught all of Greece”, and to the 19th century Classicists who believed Western civilization to be the heir of the Greek’s rational thought and philosophy, by extension, Homer was the man who formed the West’s central tale.

Of all the posts in this series, I was most nervous to write this one. Troy stands as arguably the single most well known Greek Myth, appearing in every form of media. Much of the public fascination with the story & city has grown out of mass media, and take one look at any BBC series on the matter, and romantic recreations abound. Archaeologically when we’re talking about the real city or event however, I’m not overly optimistic. Tied up in the narrative are decades of concepts such as “Homeric Archaeology”, which arguably gave rise to the field of Classics as a whole.

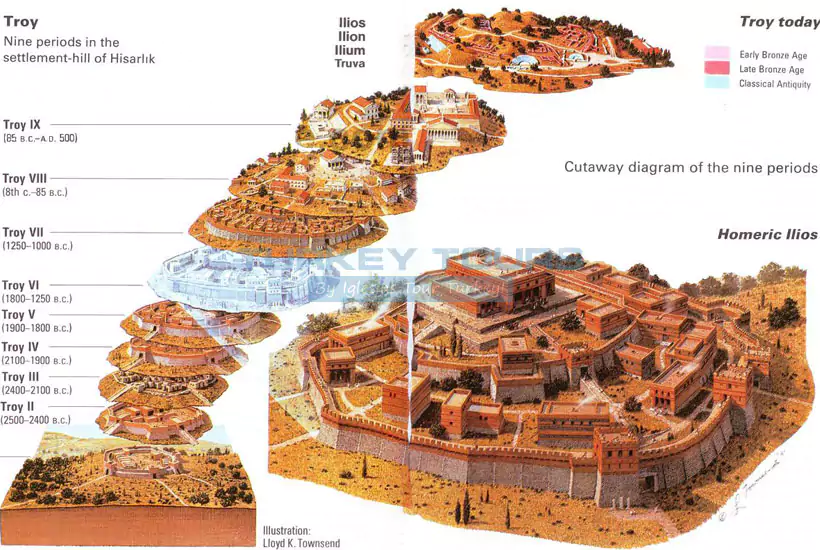

To really begin addressing the topic, we should first understand some core themes that have predominated the study of Troy & Homer more generally in historical scholarship. We should first realise that Homer’s Troy is an idealist narrative, not reflecting a historical reality. It is a composite Epic tale based sparingly and episodically on real events, most likely centred around the ancient city located in present-day Hisarlik, Turkey, known to the Hittites of Anatolia as Wiluša. The site was repeatedly destroyed and rebuilt during its 4000 years of occupation. As a result, it is divided into nine archaeological layers, each corresponding to a city and occupation phase that was built on the ruins of the previous ones.

As is standard, we can refer to these layers using numerals. Troy 0 being the earliest Neolithic settlement around 3600 BCE and Troy IX being the latest, occupied by Romans.

I’ve already mentioned parts of this city back in our episode on the Early Bronze Age. Phase II of Troy was active during the Early Bronze and served to connect large parts of the Early Mediterranean, connecting Anatolia with land routes that are going into Mesopotamia & the Aegean. It had two major peaks in its history. For the 2-300 years of the EB II, Troy had monumental walls & extensive gold artefacts and served as a major trading point in the Minoan network. It peaked in importance again around 1300 BCE, corresponding to Phase VIIa & b, at the end of the Late Bronze Age.

As well as the site itself, which can tell us about trade links and connections between Anatolia and the Aegean in different periods, its existence and discovery heralds wider themes in archaeology & how we approach studying the past. For one, the real-life existence of Troy is embedded in the Search for Homer, calling into question the extent to which we can tie literary texts to real life archaeology. This enormous debate has implications for the field of history as a whole as the use of Homer as a literal historical source was one of the founding philosophies of the entire field of Classical Archaeology. Moreover, the accuracy of Homer compared to archaeological evidence is an archetypal example of how we use texts to reconstruct the past more generally, and the pitfalls of such a methodology.

To what extent can Homer’s writings tell us genuine things about the Late Bronze Age or Mycenaean culture? While we’re dealing with Classics here, the implication has consequences for other fields such as Biblical Archaeology as well. In other words, how much does Homer really tell us about the 8th century or before and how much is simple idealism that has no real historical value outside of being a literary piece? To this day, while Phase VII does have evidence of burning that could potentially have been a siege as described in the Iliad, there is still no definitive evidence for a Greek attack on Hisarlik.

The fundamental challenge with Troy lies with its initial excavator. The site of Hisarlik was excavated by Schliemann and Calvert beginning in 1871. Under the ruins of the classical city (Troy VIII), they found the remains of numerous earlier settlements and layers, several of which resembled the Homeric literary depictions of Troy in the Iliad. Upon seeing these, Schliemann immediately declared that the Iliad & Odyssey were historical texts, presenting a real historical reality and that his site, Wiluša, was the historical Troy. This declaration pushed Homer into the spotlight, no longer was he a mythic source, but a historical one. Schliemann began arguing that Homer could be read as historically accurate and therefore be used to reconstruct the rest of Greek history and potentially find other sites. In this light of this textual primacy, archaeologists were simply chasing the texts, trying to prove what was already written.

Following his excavations at Hisarlik, with new found confidence Schliemann went across to Mycenae in 1876, believing the palace there to be the House of Agamemnon. His goal was to find the grave of Agamemnon, who was the king of Mycenae and leader of the Greek army in the Iliad. He ended up uncovering a royal cemetery containing six shaft graves, which we now know as Grave Circle A.

As I mentioned in a previous episode, among his findings was a gold death mask that he labelled as "The Mask of Agamemnon", even though we now know it to pre-date the hypothetical events of the Trojan War by nearly 400 years. Not only that, but there is currently no evidence Agamemnon ever existed as a real person, let alone ruled his kingdom from Mycenae. Equally, we have struggled to find historical support for many of the major characters from the Homeric narrative. There is no historical record of a Paris, although Laroche (1966) has noted the Luwian equivalent Parizitis appearing as a Hittite scribe name in a few Anatolian documents associated with Hisarlik.

Numerous scholars such as Robert Meagher & Peter Jackson have also derived the etymology of Helen from a Proto-Indo-European sun goddess, noting the name's connection to the word for "sun" in various Indo-European cultures. In the same light, scholars of comparative religion have noted that her marriage myth may be connected to a broader Indo-European "marriage drama" of the sun goddess, and that she is related to the divine twins.

Understanding Epic Poetry

So as we can see, even Homer may be drawing on myths during the performances of his Epics over and above historical realities. To understand the full scope of this, let’s look at the nature of Epic & Oral Poetry. A number of important works dealing with the reconstruction and performance of Epic were done in the early 20th century, mainly by linguists. One of the most important was the work of Milman Parry in the early 1900s. Parry went to the Balkans to study contemporary oral poets in an effort to understand how oral poetry worked, especially focusing on how bards and performers remembered details of their narratives and how they told them. His discoveries were foundational for our understanding of myth. He found that oral performance was seldom static, that they moved and changed a lot depending on the audience.

Orators and bards would often have episodic or linguistic lego pieces that they could fit and weave together depending on which audience they were speaking to and which themes needed more stress in each performance. Ultimately, an oral bard would change the story or sequence of events in an Epic depending on the audience to play into their local mythemes and make their performance more relevant, thereby earning more money. Naturally, some more central or known elements would have been harder to modify since they could not affect the core plot, but certain anecdotes or elaborations would be added or taken away very liberally. Many of these, such as epithets or characteristics, were often mnemonic devices that would help the poet remember sequences of events, and equally paint broader pictures for their audiences.

We must remember that Homer himself was thought to be a bard. While the historical reality of Homer as one single person is always in question, my point here is that his works are fundamentally oral poetry that would have been sung and performed, and therefore acted the same way. There was likely never one single story of Troy, but rather collections of anecdotes and episodes circulating which Homer codified together into different performances depending on where he was singing. This has wider historical implications as not all episodes could originally have been referring to the same event, or even the same conflict. We very well could be looking at different historical events being mixed together depending on different versions of a core story.

It has been common for people to argue that the core story of Troy dates back to the Bronze Age. While this isn’t out of the question, it is only half of it. The historical events may certainly date back to the period, but a lot of work has also been done on tracing the origins and emergence of Epic Tradition and Oral Performance back to Mycenaean culture. In previous episodes I mentioned the Pylos Combat Agate, manufactured in Late Minoan Crete and how its motif of battle is found across the Bronze Age Aegean potentially signalling the development of an early Epic Tradition.

Alongside this, we also find a fresco from Pylos during the Late Helladic III period that depicts a lyre player seemingly singing a tale. Some scholars have even argued that the lion hunting motif etched on the daggers in Mycenae Grave Circle A constitute a mythic narrative, although this is hard to prove. While the notion that oral poetry and epic tradition was already around during the Bronze Age long before Homer is not out of the question, to suggest that Homer is in any way a direct continuation of this tradition is speculative at best. The story of the sack of Troy may date to the Bronze Age, and may even have been performed in oral poetry during that time, but the tale surrounding it as Homer has it would have been unrecognisable. So again, to what extent can Homer truly be relied on for reconstructing Bronze Age reality?

This problem gets even more complicated when you understand OUR reception of Homer. The versions of the Iliad & Odyssey that we have today are not necessarily the versions Homer composed or even had access to. The versions of Homer that we know of today are in fact 2nd century BCE and date from the Hellenistic Period. These copies refer to a version that was likely written down around the Archaic or Early Classical period. In other words, at some point in the Early Classical period, authors and philosophers took everything they had heard or knew about Homer and compiled it into a reworked text. There are therefore numerous issues about how and when our versions of Homer were written. We equally do not know the context in which the 4th & 5th century versions were composed.

To give you an idea of why this is such a challenge, remember the nature of Epic poetry. Audiences will adhere to episodes or narrative sections that are relevant to them and often gloss over the rest. What was relevant to a 4th or 5th century audience likely was not the same as Homer’s contemporary audience. While later audiences may focus on and compile sections related to elite culture, a 2nd century audience may be more concerned with political and ethnic identity and therefore acquire or drop certain episodes. Our version of Homer is the culmination of centuries of reworks beginning in the 8th century, but also going through heavy revisions and alterations in later periods.

In other words, we are not just dealing with a 12th century copy vs an 8th century original, but also vs re-definitions during the 2nd and 6th centuries BCE.

Dating the Epic

Thankfully, back in 1991, the work of Professor Susan Sherratt at the University of Sheffield traced Homer’s textual references and contributed heavily to the establishment of a date range for his compositions & performances. Sherratt’s work compared Homer’s textual references of things like housing types, styles of warfare, burial customs and metal typologies to what we know archaeologically from different periods in an effort to date the different episodes that Homer was working from. What she found was that we are looking at a huge mix of periods.

To give a few examples, Homer occasionally mentions boar tusks as elite items that were traded between kings or generals, or in the context of adornments to helmets, which archaeologically we have evidence for from burials in the Pre-Early Palatial Period during the 16th century BCE, but no later. Frequently mentioned shield types such as the great oval or the bossed shields made from layers of hide and reinforced with metal fittings along with throwing spears correspond to what we’re seeing in the 12th century Post-Palatial, where longer range fighting styles gained prominence. Interestingly, many of the houses that Homer describes are distinctly un-Bronze Age, often having a pitched roof that was typical of Early Iron Age architecture during the 8th century BCE.

More prominently, the use of funeral pyres like that of Patroklos’ in Book 23 signals the use of cremation as a burial custom, which was very uncommon during the Bronze Age, only really coming into focus during the 10th century. Homer’s attitude towards the use of iron also changes throughout the narrative from intrinsic value item to utilitarian, signalling different periods in certain episodes where the metal was more abundant.

What we’re seeing is a story that has been in the making for centuries, with some aspects of the original remaining, but many being changed to fit a later culture. The way in which we can make sense of this is by understanding and dividing Homer’s episodes into narrative blocks that are more susceptible to change and less susceptible. Similar to how contemporary oral poets in the Balkans keep elements of the core Epic Tale and add or remove anecdotes. The core of the story being a sack of a great city by your ancient ancestors is of course difficult to change, which naturally includes many of the main characters or arcs, their epithets and formulaic lines. Alongside this, key formulaic scenes that serve as mnemonic devices for the poet probably also got preserved along with epilogues or retrospectives that carried the moral or cautionary tale.

On the other hand, things like scene or episode orders, personal speeches or invocations, incidental detail descriptions or minor characters are the most susceptible to being dropped or having their context and wording changed with culture to reflect new values.

Homer is fundamentally writing and performing for his own 8th century culture, meaning that the key themes and episodes he will be using the most reflect the wider geo-political and social landscape of his lifetime. From what we can tell from writings, the core theme at play for Homer is the notion of Panhellenism, the social action of all the kingdoms coming together to form a new Greek collective identity.

This theme is reflected archaeologically in the 8th century as we see the first traces of the Polis appearing and the Aegean collectively emerging from the Greek Dark Ages and becoming interconnected again. His focus on elite culture is also a distinctly 8th century concern, as we see the re-establishment of strong hierarchies in village sites. Local elites may well have used Homer’s performances as ways to re-establish links with older, ancestral rulers and legitimise their new authority. Homer therefore tells us much more about what people are interested in during the 8th century BCE than he does anything during the Bronze Age.

Sources

Sherratt, E. S. 1990: Reading the texts: archaeology and the Homeric question, Antiquity 64, 807‑24.

Bennet, J. 1997: Homer and the Bronze Age, in I. Morris & B. Powell (eds.) A New Companion to Homer, 511‑34.

Mac Sweeney, N. 2018: Troy: Myth, City, Icon, London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

Morris, I. 1986: The use and abuse of Homer, Classical Antiquity 5, 81‑138

Whitley, A. J. M. 2013: Homer's entangled objects: narrative, agency and personhood in and out of Iron Age texts. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 23(3), pp. 395-416.

Stocker, S. R.; Davis, J L. 2017: The Combat Agate from the Grave of the Griffin Warrior at Pylos. Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. 86 (4): 583–605.

Meagher, R E. 2002: The Meaning of Helen: In Search of an Ancient Icon. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. pp. 46.

Jackson, P. 2002: Light from Distant Asterisks. Towards a Description of the Indo-European Religious Heritage. Numen. 49 (1): 61–102.

Laroche, 1966: Les noms des Hittites. 325, 364; cited in Watkins, C. 1984: The Language of the Trojans: Troy and the Trojan War: A Symposium Held at Bryn Mawr College.

Gunderman, R. 2021: Heinrich Schliemann. archeological pioneer. Indianapolis Business Journal. 42 (7): 13A.

Korfmann, M, O. 2007: Troy: From Homer's Iliad to Hollywood epic. Winkler, Martin M (ed.). Blackwell Publishing Limited.

Jablonka, P. 2011: Troy in regional and international context. In Steadman, S; McMahon, G (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia. Oxford University Press.

Don't miss a post!

Sign up to get notified of when I upload as well as any new classes delivered to your inbox.

I hate SPAM. I will never sell your information, for any reason.